January 1 2023 marked the centenary of the birth of Ousmane Sembène, the Senegalese novelist and film maker hailed as the “father of African cinema”.

Over the course of five decades, Sembène published 10 books and directed 12 films across three distinct periods. He has been celebrated for his beautifully crafted political works, which range in style from the psychological realism of Black Girl in 1966 to the biting satire of Xala (The Curse of Impotence) in 1974.

Since his death in 2007, Sembène’s status as a pioneer has been further cemented. But the sheer variety and richness of his work – his ability to reinvent himself as an artist – has often been overlooked. On the occasion of his centenary, it’s worth looking at what made him such a remarkable creative presence.

THE NOVELIST: 1956-1960

Unlike many of his literary peers, Sembène did not come to writing via the colonial education system. In fact, he left school early and was largely self-educated. He was born into the minority Lebou community in the southern Senegalese region of Casamance. His father was a fisherman. He later moved to the colonial capital of Dakar.

After serving in the French army during World War 2, he moved to France in 1946. Employed as a dockworker in Marseille in the 1950s, he developed a love for literature through the library of the communist-affiliated trade union General Confederation of Labour.

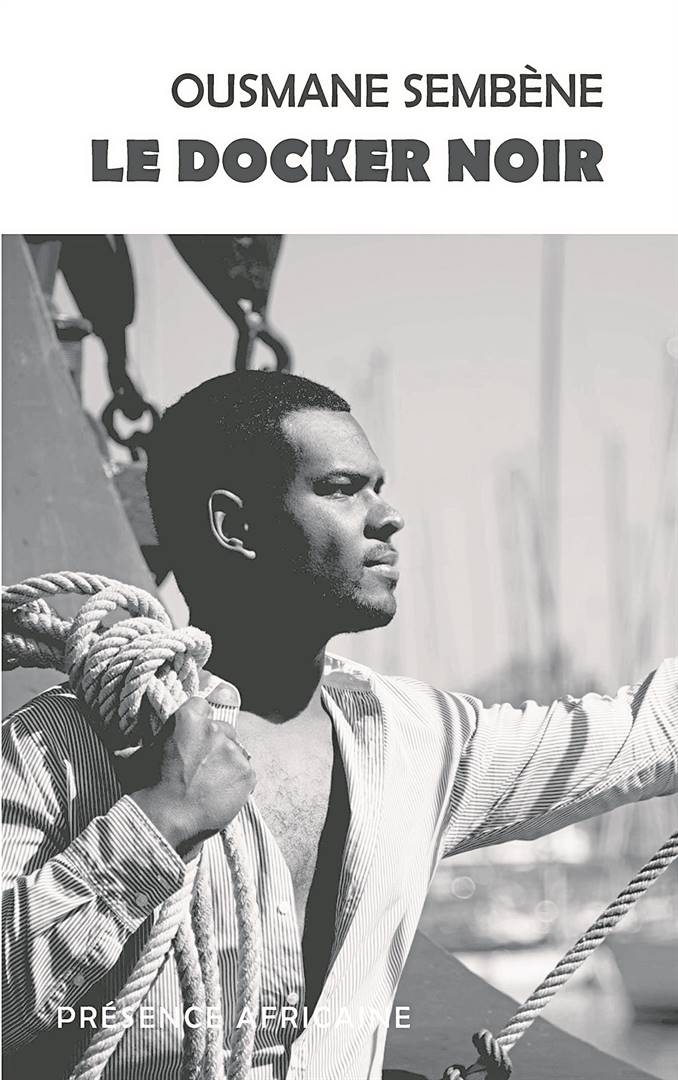

His first novel, The Black Docker (1956), self-consciously explores the difficulties faced by a working-class black writer seeking to become a published author.

God’s Bits of Wood is often described as classic Sembène text, politically committed and realist in style. It proved to be the high-water mark of his exploration of literary realism.

In 1960, he returned to Africa after more than a decade in Europe to tour a continent emerging from colonial domination. He famously stated that, sitting on the banks of the Congo River, watching the teeming masses, most of whom could not read or write, he experienced an epiphany. If his novels were inaccessible to many Africans, cinema was the answer. And so he set about becoming a film maker.

Novelist and film maker: 1962-1976

After studying cinema in Moscow, Russia, Sembène directed his first short film, Borom Sarret (The Wagoner), in 1962. Depicting a day in the life of a lowly cart driver, the film provides a stinging critique of the failures of independence in Senegal, cast as the transfer of power from one governing elite to another. Like most Francophone African countries, Senegal had gained its independence in 1960. It would be governed for the next two decades by the Socialist Party, led by the poet Léopold Sédar Senghor, who sought to maintain close political and cultural ties with France.

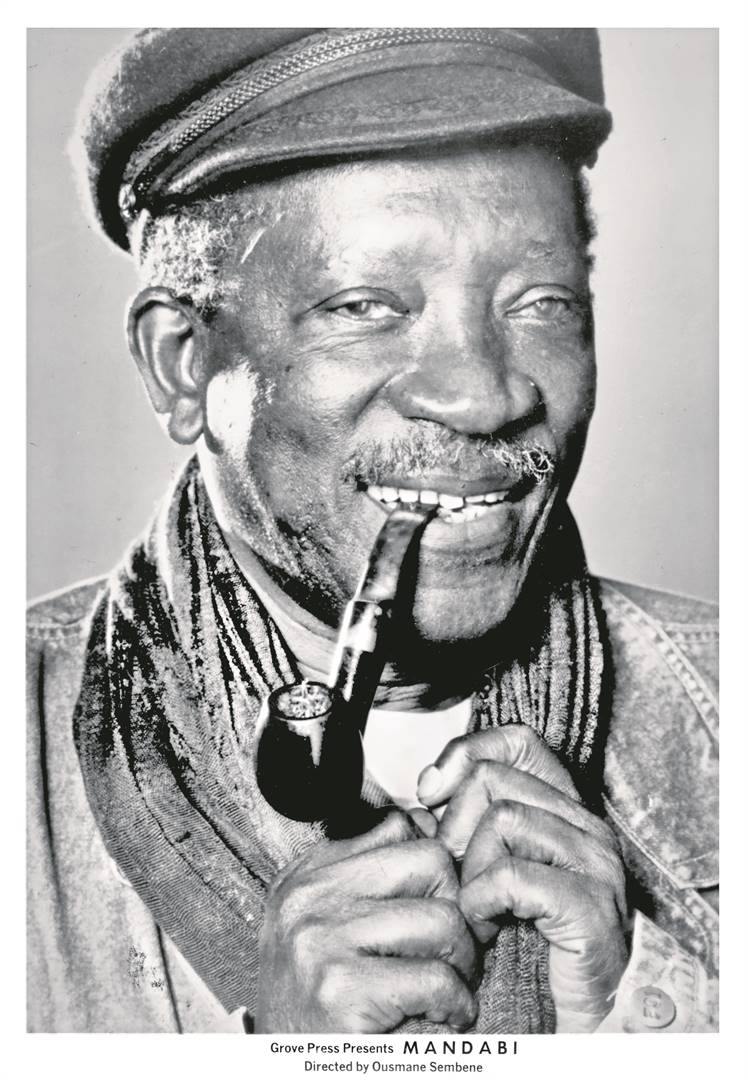

Between 1962 and 1976, Sembène published four books and directed eight films – works of an incredible aesthetic diversity. Indeed, this may rank as the single richest period of artistic productivity of any African writer or director in the post-colonial era. He chalked up a series of pioneering firsts by a black African director: first film made in Africa (Borom Sarret), first feature film (Black Girl) and first film in an African language (Mandabi).

READ: African film 101: The names you need to know

He began to gain international renown, but there was little opportunity to see his work at home. Mandabi (The Money Order), for example, won a prize at the Venice Film Festival but was not released in Senegal, where it was criticised by the government for presenting a negative vision of the country.

Between 1971 and 1976, Sembène made his most ambitious trilogy of films: Emitaï, Xala and Ceddo. Each was driven by strong storylines.

But most important to Sembène was a film’s ability to condense social, political and historical realities into a series of searing images. These often blurred the boundaries of space and time.

In Ceddo, he collapsed several centuries of history into the life of one Senegalese village, leading to a struggle for power between animism, Christianity and Islam. The last asserts its dominance through the barrel of a gun, a controversial stance in a country that was over 90% Muslim by then. Ceddo was banned by Sembène’s arch-enemy, Senghor. He would not make another film for more than a decade.

Wilderness years to a late flowering: 1976-2004

After a decade spent largely in the creative wilderness, Sembène experienced a late flowering from the end of the 1980s onwards.

This period saw him reach a new generation of audiences. His later works were less ambitious aesthetically, but no less powerful.

Moolaadé (2004) was a scathing denunciation of female genital mutilation in rural west Africa. In it, the forces of change oppose conservative, patriarchal authority.

Sembène today

Since his death, we have learnt more about Sembène’s life and career through the painstaking work of his biographer, Samba Gadjigo, who co-created the documentary Sembène! (2015).

Sembène’s films still matter today, not only because of the ongoing relevance of many of the social and political issues they dealt with, but also because he was able to create a film language that spoke powerfully to audiences around the world.

He forged a career that lasted five decades when many of his contemporaries struggled to make more than a handful of films. That creativity and longevity helped to shape African cinema in complex ways: contemporary directors may follow in Sembène’s footsteps or choose to reject his politically committed style, but his legacy cannot be ignored.

Murphy is professor of French and postcolonial studies at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland. This article was first published in The Conversation

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners