It was his brother’s funeral and it was clear to everyone there that Royd Tolkien was nervous and heartbroken. But as he prepared to deliver a eulogy about his beloved Mike, something happened that left assembled family and friends frozen in horror.

It almost seemed to happen in slow motion: walking up to the front of the crematorium chapel, Royd tripped, knocking his head against the podium.

For a few moments an awkward silence prevailed and then a friend rushed forward to help. But Royd, who is the great-grandson of The Hobbit author JRR Tolkien, quickly recovered, picked himself up, positioned himself at the lectern and reached into his pocket. The piece of paper he pulled out and held up had two words on it. “TRIP OVER,” it said.

Tripping up at his funeral was the first task on a 50-item bucket list that Mike, who was 39 when he died, had assigned Royd. And it was perfect timing.

“I looked up and everyone was trying not to catch my eye, and wondering what to do. But then I got out the piece of paper, and there was such relief – and a feeling of, ‘Oh, that's typical of Mike . . .’

“But it was a beautiful thing. It wasn't to make me look like an idiot – well, maybe there was an element of that – but he knew it would be a terrible situation for everyone there and that this would break the ice and take the edge off.”

The bucket list was assembled over a couple of years when Mike was growing increasingly ill with motor neurone disease (MND), a fatal condition that affects the brain and nerves and for which there is no cure.

Royd (51) knew the list existed but had no idea what was on it; the tasks were revealed to him one at a time after Mike's death. Some things were meant to challenge him (a bungee jump, flying a plane, handling a tarantula), some were emotive throwbacks to times the brothers had spent together.

“And some things were, bluntly, meant to make me look like a t*t,” Royd writes in his book There's a Hole in My Bucket (snowboarding in nothing but a leopard-print thong and a cowboy hat, or asking strangers in the street to dance). “And a few were simply things that Mike really wanted to do himself.”

But Mike couldn't so his brother did them on his behalf.

Royd, a film producer, is waiting for me at the station in the English town of Chester with a grin on his face. He is a likeable man with the look of someone who is always ready to be amused.

We discuss where to go – he is reluctant to take me to his house, the address of which he'd like to keep quiet, presumably to deter people from turning up dressed as hobbits.

He suggests a local restaurant. “Or,” he says hopefully, “we could go to my climbing wall?”

Seeing me wince, he adds, “There's a café there and lots of space to sit down and talk.

The Boardroom, just over the Welsh border, is Tolkien's favourite hang-out. It's near his home, and he goes there a few times a week, often with his son Story (26) (named after the American astronaut Story Musgrave).

Huge climbing walls stretch up to the ceiling, with impossibly tiny foot and handholds. People – mostly men – hang off them in painful and unlikely-looking positions. It appears extremely challenging and, to me, a bit pointless.

“We'll get you up there!” Royd says encouragingly. “Get you a harness and send you up that wall!”

No you will not, I say. I'm not the one with the bucket list.

The list Mike devised for Royd was largely completed over four months, in New Zealand, a country with which the brothers had an association. Royd had been there several times, first to appear in an uncredited role in The Return of the King, the final film in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, adapted from his great-grandfather's work. Another uncredited part, in The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, was cut, much to Mike's amusement.

Mike’s girlfriend, Laura, was the custodian of the list, and the whole project was co-ordinated by a producer of the film that was made about the endeavour.

We sit at an outside table, where Royd tells me he built a climbing wall at home during lockdown.

“Climbing is a great thing to do – and really healthy,” he says, drinking coffee and puffing on a roll-up cigarette. “Mike would have loved it. He was an adrenaline junkie, really active. Snowboarding, wakeboarding, semi-pro paintballer, downhill mountain biking – he was totally into outside life. Healthy, fit, constantly pushing himself. I just never really did that sort of thing. I was quite content to just do . . . gardening.

“We were really competitive – we were always trying to get one over on each other. But that adrenaline sort of stuff – it just hurt, I didn't see any reason to do it.”

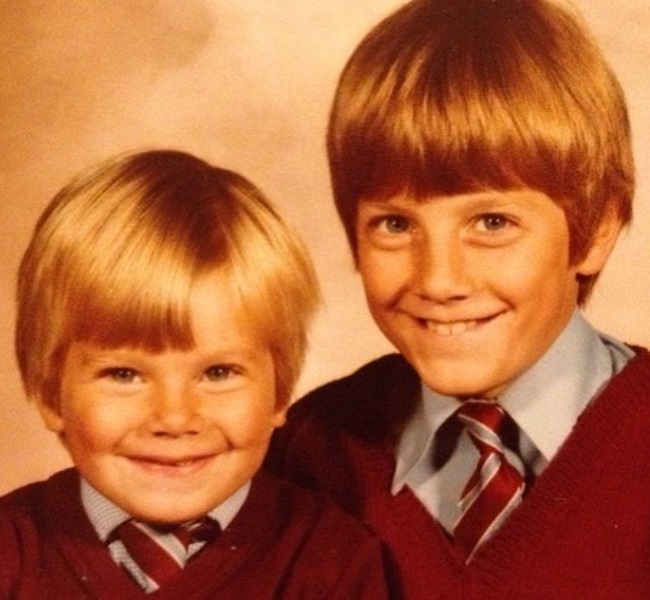

Mike, Royd and their sister Mandy grew up together in Flintshire. Their mother is Joan Tolkien (76), JRR Tolkien's granddaughter, who now lives in Oxford; their father, Hugh Baker (81), lives in Chester.

They split up when Royd was a teenager, and he took the name of Tolkien.

“I just felt close to that side of the family. For holidays we'd stay at Aunt Prisca's house near Oxford [JRR Tolkien's youngest child] and every year there was an event called Oxonmoot for members of The Tolkien Society, and we'd go there for the celebrations.”

The two brothers were always very close and lived near each other.

“He was the best brother you could wish for,” Royd says. “Happy, fun, full of drive, never miserable or moping, trusting – I looked up to him, despite him being five years younger.”

It was in November 2010 that Mike got ill. He was 35 and had barely had a day's sickness in his life.The illness started with a high fever and flu-like symptoms, then he developed weird cramps in his calf and weakness in his hands. He consulted a doctor but carried on with life, continuing work as a printer and co-parenting his eight-year-old son, Edan, with his ex-wife.

The following year the brothers went snowboarding in Avoriaz in the French Alps with a group of friends, and Royd noticed Mike was having trouble getting up on his board. Months of medical consultations followed.

“The frustrating thing about MND is that there is no single test to prove its existence, it's more a case of ruling everything else out,” Royd says.

In April 2012 the diagnosis finally came. That day, Mike and Royd talked about the reality of the diagnosis – the bleak prognosis (the average life expectancy after an MND diagnosis is just 18 months), the inevitable hideous illness, the fact that Mike wouldn’t be able to see his son grow up, and the enormous gnawing void that Royd would feel after the loss of his brother.

It was the only time, he says, that they talked about death, and the only time they showed such a degree of emotion. They held each other and sobbed uncontrollably.

The bucket-list idea originated more as a plan of things they wanted to do together with the limited time they had left.

“To go camping in Norway for the last time, to go snowboarding together in Avoriaz, and to New Zealand.”

They had only been there together once, while making a flight-safety video for Air New Zealand.

Sadly they didn’t get to return, but that was where Mike set most of the bucket list. It was a place he knew Royd loved, and a place that specialises in the kind of high-adrenaline daredevil sporting activities that he had in mind. So he started making an agenda of things for his brother to do after his death.

And then at some point he said to Royd, “You make films – make a film of this.”“He knew what it would be like when he passed away. We didn't talk about it – we only ever discussed it on the day of his diagnosis. But he knew what it would be like for me and he knew I would need something to focus on.”

The bucket list helped Royd to grieve for his brother. It was a huge challenge – a documentary that needed to be financed, meticulously planned, shot, edited, delivered and released.

But knowing it was a way to raise awareness of the cruel condition that is MND, a way to help sufferers and their families, it was a project Royd was determined to fulfil. Because he knew that at some point soon, not only was he going to be left without a brother, but he was going to be left without anything to do, as for the last three years, along with Laura, he had been Mike's full-time carer.

Caring for Mike was a demanding job. MND affects people differently (British cosmologist Stephen Hawking lived with the condition for decades, but this is rare). Mike went downhill fairly fast, and in 2014, when things were really bad, he moved into a hospice. But Royd and Laura learnt how to use the equipment – breathing machines, hoists – and were able to get him back home.

“For the first time in my life I had something that I felt I was good at,” he says. “I did it because I wanted to, I was happy to do it and it felt like I really knew who I was.”

Effectively, he did the day shift and Laura did the night shift.

“I would get there at about eight or nine in the morning from my house 10 minutes away. He needed everything doing for him in the latter part of his illness – feeding, massaging, changing, shaving, cleaning the oxygen mask. Towards the end he couldn't even blink – that's what it does to you, that disease.”

It was hard to watch his brother’s steady decline.

“But no matter how tired I would feel, I would never let that show because I could go home at 9pm, I could have a bite to eat, sleep – but he could barely move. And during the most terrifying challenges from the bucket list, I would think, this is just temporary. The sheer terror, or the gut-wrenching awkwardness – it's just temporary and then I can go back to normality.”

Mike died on the morning of 28 January 2015.

Royd hadn’t forgotten about the bucket list. After his dramatic funeral trip there was the snowboarding in Avoriaz – wearing that leopard-print thong and cowboy hat.

And then, in February 2017, he went to Heathrow airport to catch a flight to New Zealand and in the departure lounge he was handed a Gandalf outfit (the actual costume worn by Ian McKellen in the films, thoughtfully supplied by the Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson) and told he had to introduce himself to people getting on the plane in character.

The fun continued. On the plane he was told, via an iPad, that he needed to get a tattoo. He already knew what it would be: a winged scarab beetle, the same one that Mike had.

Once he'd arrived in Auckland, that was easily done. Next on the list was a haircut. This he found particularly traumatic. Royd had long flowing hair, of which he was rather proud, though his brother had teased him constantly. “Cut your hair,” he'd say. “It looks stupid.”

But Royd was aghast at the suggestion. In a panic, he rang his son who said, “Dad! It's hair – it grows back. Do it!”

So he did it. Because whenever possible, the list had to be checked off in order, though the production company co-ordinated the schedule according to locations.

“I didn't know on a daily basis what would happen. Sometimes it was two or three tasks in a day, then there might be a day off.”

Royd really had to dig deep for the physical challenges which included abseiling and white-water rafting; sitting in a plastic chair and tipping backwards off a 60-metre high cliff in order to swing across a canyon on a rope; wearing a pink tutu to do the Nevis Highwire bungee jump; and flinging himself off a bridge.

The list has not, he says, given him an appetite for these pastimes.

Some things were specifically directed at confronting his particular fears – such as handling the tarantula – and some were just downright cringe-inducing: “Dress as a hippy and spread some love”; “Set up an amp in a town centre and play some music, then offer to dance with people to make them happy.”

In one of the most agonising, Mike wrote, “You think you're funny. Find an open-mic comedy night and see how many laughs you get.”

So Royd did just that. In a gay bar in downtown Wellington. With one hour's notice. A comedian had been laid on to help, but he was late so they only had 20 minutes to plan the routine.

Royd didn't think much of the guy's suggestions, and was desperately scraping the barrel for material. Having just done challenge number 16, the tarantula, he decided to focus on this as his comedy subject.

It being an open-mic night, there were several other comedians. Royd was waiting in the wings. “So . . . spiders,” said the act on stage before him. “Man, I hate spiders. Who's afraid of spiders?”

Royd couldn't believe it. It was such a coincidence that he thought it must be part of the set-up, but it wasn't. When it was his turn, he struggled through his 15 minutes making terrible, lurid jokes and then tried to leave the stage, only to be told he still had three minutes to go.

Sounds excruciating, I say. Has the list at least made you better at handling embarrassment?

“Yes, I'm definitely less affected by it. I used to do everything I could to avoid being embarrassed.”

The saddest tasks for Royd were the ones that Mike would have loved doing, things that they had hoped to do together but not managed before he became too ill – fishing and canoeing in New Zealand.

“And the best tasks were the ones that made me reconnect with Mike – revisiting an area that we'd been to together.”

And the worst task?“There was no worst task. Well, maybe the last one.”

He has never completed the final item on the list: to scatter the rest of Mike's ashes at Machu Picchu in Peru, where he had always wanted to go.

Royd had already scattered some in other places – mostly at Moel Famau, a hill near his home in Wales, with some in Avoriaz, where they went snowboarding, and some in Norway.

But when he got to Machu Picchu, he found that he didn't want the journey to end. He sat there for a couple of hours, nursing the little box; he rang Laura, and Edan, and Story, and his father. And he decided that he would do it at a later date, when they were all with him there, and not just for the sake of a documentary.

“I don't want the list to be over. Though even then it won't be over – because his journey still continues, through the book and the film. His legacy will live on.”

The bucket list, he says, enabled him both to grieve and to get out of the rut he found himself in after Mike's death.

'I'm still scared of spiders and I'll never do a bungee jump again, but I can't wait to go back to New Zealand – and I would probably do some of the things on the list again, just to keep that connection with Mike.

“Because if I didn't, I know Mike would be rolling his eyes, saying, ‘Oh come on Royd . . .’ ”

There's a Hole in My Bucket: A Journey of Two Brothers, by Royd Tolkien will be published in August. The film, There's a Hole in My Bucket, will be released on Amazon the same month.

Source: THE TELEGRAPH

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners