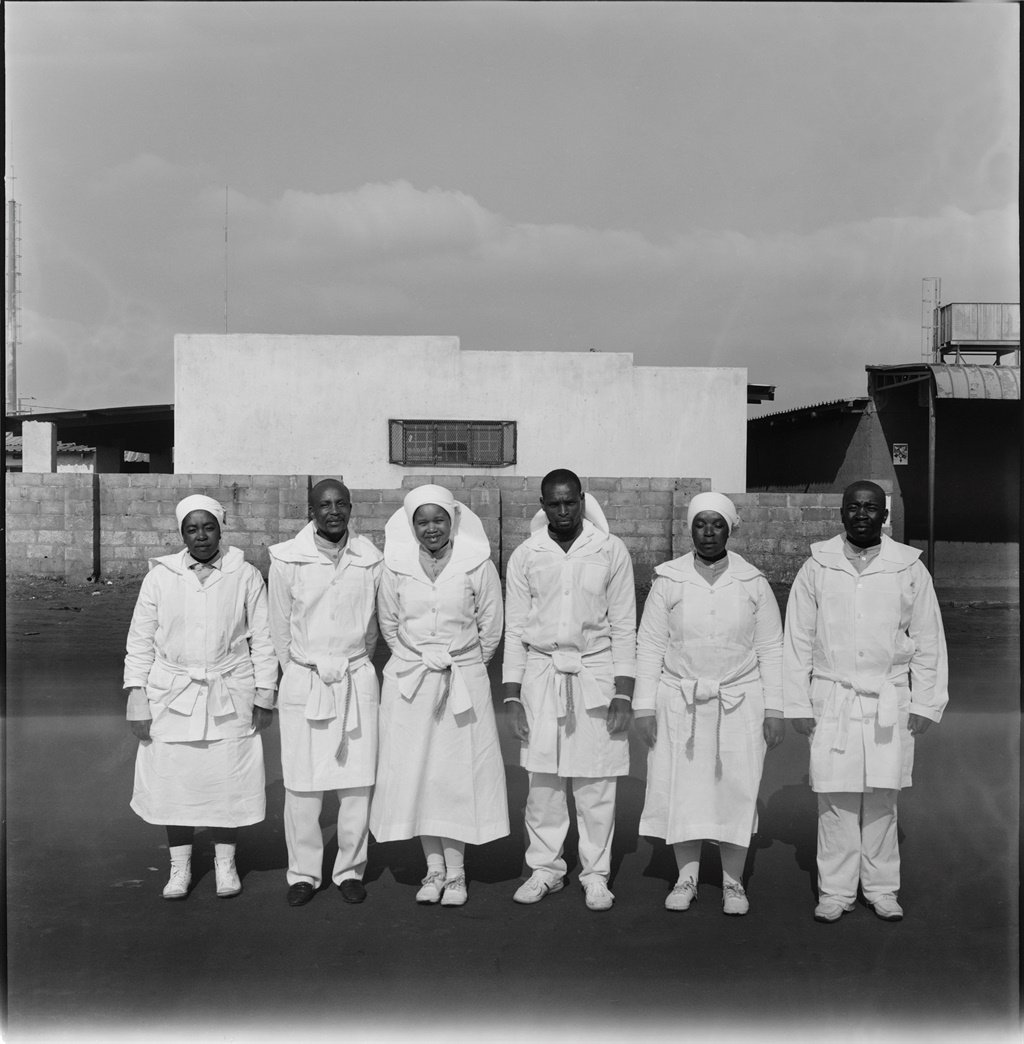

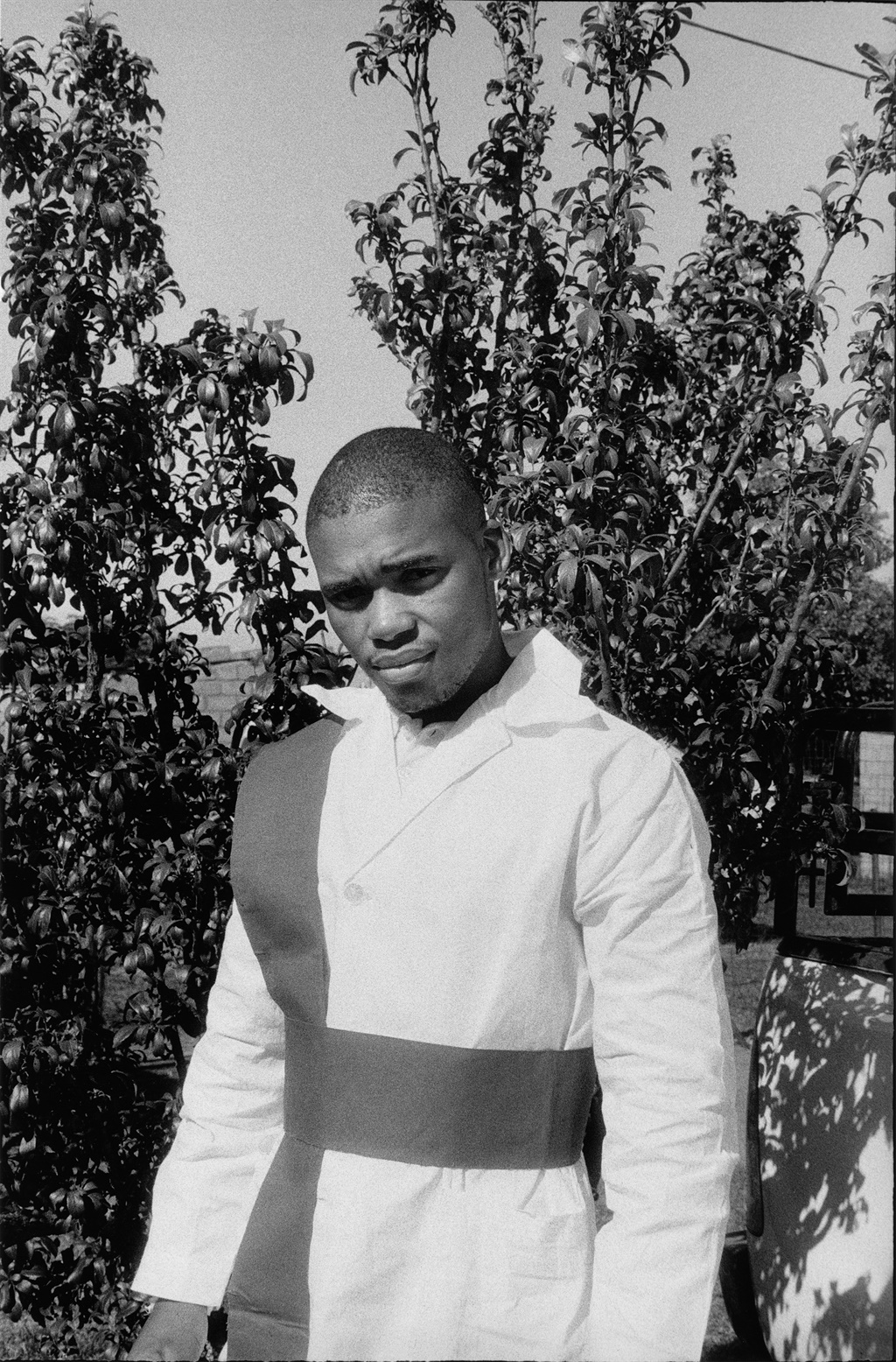

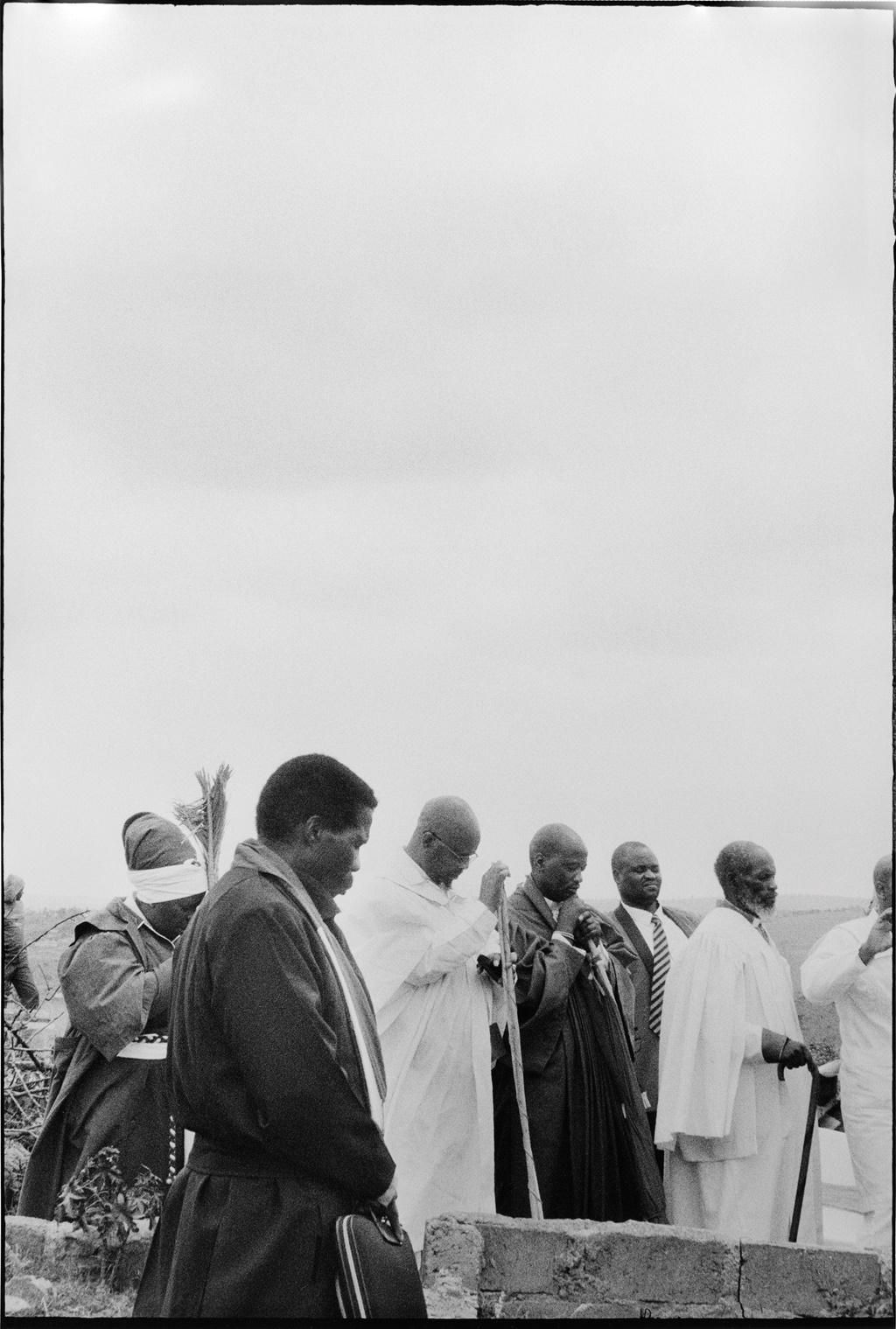

In his new exhibition, Umlindelo wamaKholwa, at the Wits Art Museum, Johannesburg-based photographer Sabelo Mlangeni presents a series of 52 prints depicting Zionist Christian Churches (ZCC) in diverse parts of South Africa.

Zionism is the country’s largest popular religious movement with some 15 million members.

The exhibition title in isiZulu can be crudely translated into English as Night Vigil of the Believers, but the politics of language means words borrowed from one language might lose complex historical resonances when translated into another. What’s so often missed in linguistic translation can perhaps find a second life in the visual language of photography.

Mlangeni’s carefully curated images offer viewers intimate ways of seeing, knowing and being in a spiritual world that can feel familiar and strange, universal and particular.

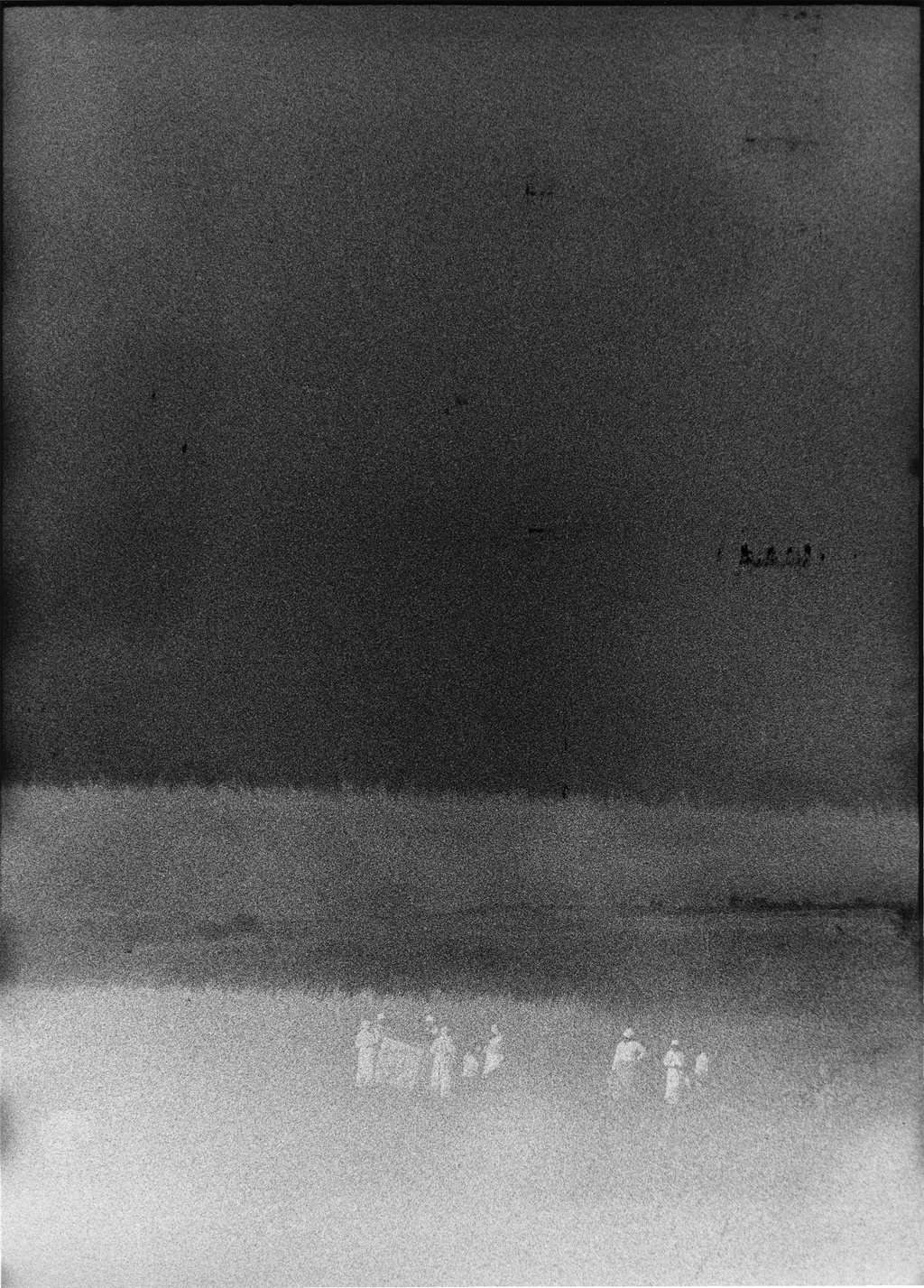

Umlindelo comes from the root verb –linda, which means “to wait”. Mlangeni has stated in previous interviews that the nuances of waiting are central to his body of work.

“I’m interested in the Zion Church as a community, where people gather like spiritual sisters and brothers. And ukulinda/umlindelo is very central to this; it’s a time when a community is created by the experience of waiting together.”

Waiting and watching in the night is not an act that views time as static or meaningless, but one of productive and purposeful social and spiritual formation. For Mlangeni, communal waiting enriches spiritual experiences of space, place and time.

The choice to have the majority of Mlangeni’s images printed in black and white is a testament to this fact.

“One of the things I like about working in black and white is the timelessness of the photographs. So, sometimes when you look at these photographs, you have a sense of a certain time. A time before. For me, this became very important; it took me back to a time when amaKholwa [the believers] first came about in South Africa. And also, what was the opposite of that? So it became very important to think about amaQaba, the people who resisted Christianity and Western civilisation. So you get lost in time. That’s something I like, that you have to read and get really inside the images.”

Many of the images are taken in the artist’s home town of Driefontein, a site where the first Zionist missionaries from Zion City in the US focused their proselytising energies in the late 19th century.

The notion that one is “lost in time” may be interlaced with the importance Zionists place on “getting lost” in open landscapes. The creative use of open space is one of the movable borders and boundaries that expand or contract with the historical and present social stratification of South African land. The relationship between waiting, nature and spirituality in the Zionist context is one of opening and closing borders between the seen and unseen worlds. The act of waiting necessitates the passage of time, expectation for the future, and a moving present that paradoxically grapples with what is both set before and ahead of it.

In a Christian context, waiting is a heedful watching, the foregoing of foolish spiritual sleeping in exchange for the reward of divine glory. It intertwines expectation with a knowledge born out of a mystical faith and trust, a readiness to take action at the right time, or learning to be content with God’s provision and timing.

Or, as Mlangeni has said about some of his images, the Zionist practice of waiting and vigil “talks about a certain time when things were a little bit lighter for African people. So in a way, that’s political: how things became a little bit darker. Yet when you talk about night, you’re waiting for the day.”

- Umlindelo wamaKholwa runs at Wits Art Museum until October 28

- Lim is a PhD sociology student at Yale University. She’s on a Fulbright-Hays scholarship in Johannesburg

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners