The first installation I saw as I walked into Joburg’s Goodman Gallery was a collection of microphones looming over a pine box – a makeshift seat, I realised. The absence of someone who would speak into the microphones was notable.

Above and behind the microphones, there’s a line of text on the wall: “Speaking and listening seem to be an analogous project. A project between those who speak and those who listen; a negotiation between the speakers and the listeners: it seems one can only speak, if one’s voice is listened to.”

Thus begins Grada Kilomba’s first solo exhibition in Africa with her 2017 installation called The Simple Act of Listening.

The exhibition, titled Speaking the Unspeakable, uses video and sound installations, staged readings, text collages and other formats.

Kilomba explains that she pulls knowledge relegated to text into the exhibition, thereby “performing” her own writing and feminist theory. Using this performance, Kilomba works to interrupt the often sterile, silent “white cube” of traditional art galleries with a lyrical, visual language comprised of historically silenced voices and narratives.

A work that struck me at the exhibition is The Desire Project, which is comprised of a three-channel text-based video installation. Kilomba’s thoughts on the invalidation of knowledge and experiences of colonised subjects is explored, as is the framing of colonial knowledge as inherently objective.

Kilomba stresses the positionality of those who speak, and how their/our knowledge is invalidated depending on their/our position when it comes to race, gender and sexuality, as well as a host of other factors.

READ MORE: 16 ideas for a gallery wall

“I write as an obligation to find myself,” the text of The Desire Project reads, and Kilomba seeks to be the describer of her experiences – not the described.

Kilomba was born in Portugal and lives in Berlin, Germany. She explored her work with exhibition curator Lara Koseff in a recent public discussion, and Kilomba provided me with further details in an interview I had with her later.

Out of respect for and in acknowledgement of her desire to be the describer and not the described, I have chosen to use her words verbatim as far as is possible.

"I find that very exciting; that when we start telling stories or create a visuality to stories that have been silenced, that sometimes the platforms are inadequate to react to those new stories. Traditional and classic spaces often try to tell stories in a particular format, and then we come with a new perspective and a new language that is a hybrid of disciplines,” she says.

“I think many marginalised bodies have to find new languages and new artistic practices to express ourselves, and we also need to find spaces where we can speak these languages. Most of these [gallery or museum] spaces are dominated spaces where we were once denied entrance, or where our works are not to be seen, or where our work is not in accordance with the ‘white cube’. I think we need to go into these spaces and experiment as we seek to create new languages that were not there before.

READ MORE: Everything you need to know about collecting art

“I think it’s important that we enter these spaces and occupy them, interrupt them, disrupt and appropriate them; and to bring a new agenda and to change the agenda. I think that’s when art becomes transformative – when it’s able to bring questions that were never there before.”

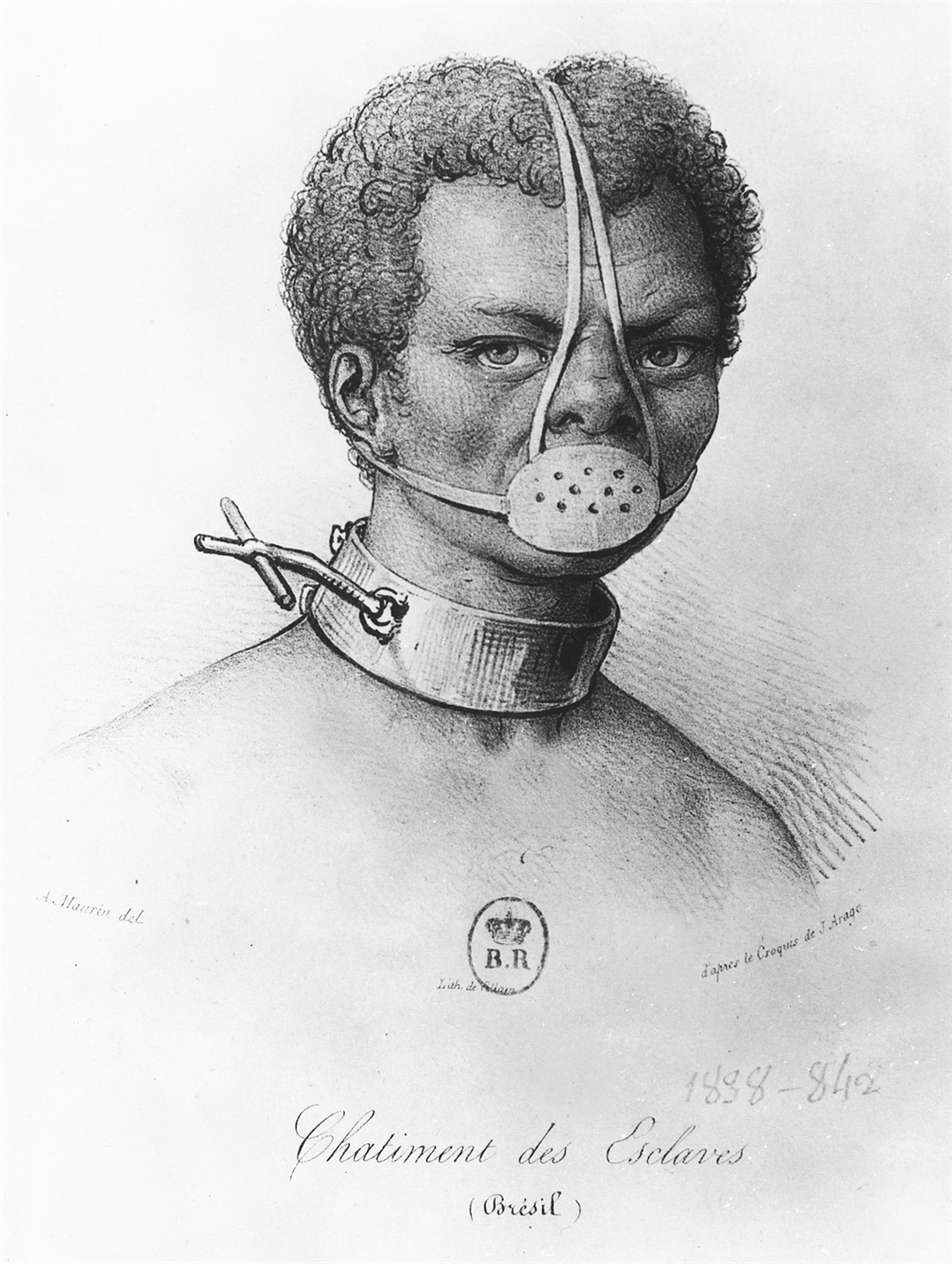

Another particularly jarring piece Kilomba includes in her exhibition is Table of Goods, an installation comprised of a mound of soil with pockets filled with coffee, sugar, dark chocolate and cocoa – all of which are goods associated with and produced by past and modern-day slaves.

The mound, which resembles a grave with its surrounding white candles, is a visual representation of all those things that enslaved people were forbidden from consuming as they worked on plantations around the world.

To physically prevent these enslaved people from consuming these products, many were forced by their colonial owners to wear a gagging mask. The masks had the further effect of preventing enslaved people from speaking or from consuming dirt as a way to commit suicide, thereby reclaiming their agency as subjects as opposed to objects owned by their masters.

READ MORE: Bollywood movies taught me so many life lessons - here are some you might not expect

“One aspect of the work that I wanted to do was to look as these forms of oppression that are like ghosts; that keep interrupting our lives, keep bringing the past into the present and keep interrupting our everyday life – just as ghosts do, symbolically – and bring fear into your life where it shouldn’t be.

So I started working with this metaphor of a ghost – slavery is a ghost, colonialism is a ghost, sexism is a ghost. All these oppressions are violent ghosts that interrupt your life and scare you.

“We need to talk about these ghosts and give them a proper burial. We need to name them, put them in the right place, like a graveyard, and give them a dignified burial so that the ghosts disappear. The ghosts are there because these [forms of oppression] are not named.”

- Kilomba’s exhibition will be hosted by the Goodman Gallery until April 14

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners