About the book:

She has been fairly media averse and hasn’t granted many interviews in the past few years, but taking a closer look at her history does provide some clues about the kind of leader she is.

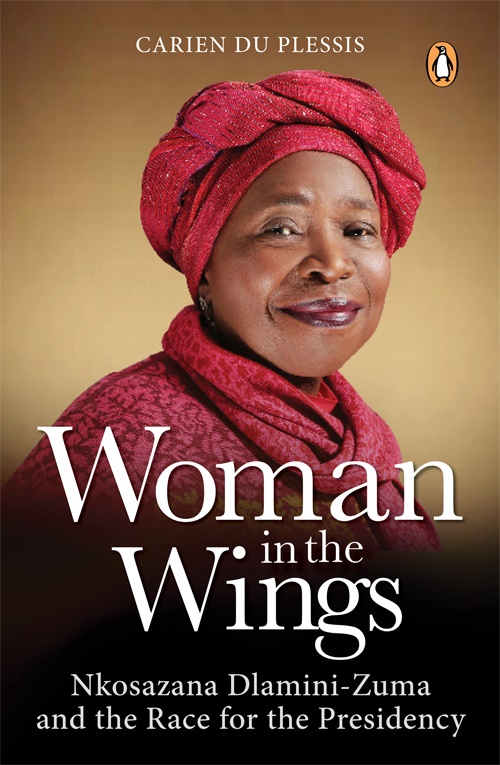

In this book, journalist Carien du Plessis looks at Dlamini-Zuma’s early years, education and involvement in the struggle; her role as a cabinet minister under all four presidents of democratic South Africa; and her achievements as African Union Commission chairperson.

The excerpt below was published with permission from Penguin Random House South Africa and is available from all leading bookstores.

Over the years the epithets have stuck. Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma was brusque, distant, difficult. She championed rights for women and positions for them in places of power, yet her relationship with men was complicated.

Was she a puppet during Thabo Mbeki’s presidency? Had she run to the ‘big men’ when the heat was on? Had she aligned herself too closely to her disgraced former husband, President Jacob Zuma?

As the ANC entered the final months ahead of its elective conference, the questions became ever more pressing; and answering those questions became ever more difficult.

There were tangled threads everywhere.

When Bathabile Dlamini was elected leader of the ANC Women’s League shortly before Women’s Day in August 2015, it wasn’t only the women who were celebrating. On the sidelines, three of South Africa’s ‘big men’ in politics looked on with satisfaction.

She was also their choice.

The lobby group, which emerged in the months before the conference, got nicknamed the ‘Premier League’ because it comprised three premiers: Ace Magashule (Free State), David Mabuza (Mpumalanga) and Supra Mahumapelo (North West).

All three were supporters of Jacob Zuma.

(As an aside, it has to be noted that in 2017 Mabuza subsequently appeared to publicly withdraw his support for Zuma and there were reports that he was threatened with arrest unless he endorsed Dlamini Zuma for ANC president. He apparently had a problem supporting her because she cancelled his friend Robert Gumede’s tender all those years ago.)

In the months leading up to the conference, branch members said there were directives and material incentives offered to delegates willing to vote for Dlamini Zuma. She was highly supportive of Zuma.

Of course, the three premiers denied campaigning for her.

READ MORE: News 24’s extract - Woman in the Wings: NDZ and the race for the Presidency

A few months later, the ANC Youth League elective conference followed a similar pattern.

And then, despite a moratorium in the ANC on nominations for the presidency, the Woman’s League swept aside this rule. In early January 2017, just short of twelve months ahead of the ANC’s elective conference, they nominated Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma as their candidate.

Soon the three premiers were also singing her praises. And equally quickly came accusations that she was a mere front for the interests of these men, and Zuma in particular.

It came down to the question: how much of her own woman was Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma? As with so much of her life, the conclusion proved elusive.

Shortly after Donald Trump’s inauguration as the US president, she attacked his ban on refugees from Somalia, Libya and Sudan.

‘The very country to whom our people were taken as slaves during the trans-Atlantic slave trade, has now decided to ban refugees from some of our countries. What do we do about this?’

She said this in her opening speech at the AU’s January 2017 summit. It was scathing, but what was she really going to do about it? It could have been meant to bolster the perception that she was ready to stand up to ‘big men’.

Equality for women in government positions was one of the principles that she had consistently advocated and fought for.

She gave it as much attention in her cabinet portfolios as she did at the AU. But throughout 2017 it became a more central focus. Some in the ANC and its leagues, as well as President Zuma, used the call for the country to have a female president as a way of enhancing her status.

WATCH: Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma sworn in as MP

In turn she has fed these sentiments into speeches when addressing women, calling on them to make themselves available for leadership positions. She also used phrases such as ‘radical economic transformation’ and demanded the expropriation of land without compensation, both ANC mantras espoused by Zuma’s lobby group.

The latter would require a change to the Constitution.

Nor was she above using the ‘race card’ against detractors. When the Sarafina II scandal broke she lashed out at her critics as ‘whites who just want to pull black people down’.

Then Mandela supported her by accusing the ‘white owned media of victimising her’. With the Virodene outrage the next year she labelled her white critics ‘racists’ and if a black person berated her she saw it as a personal attack.

During the struggle years she had dismissed white people as a ‘fact of history’, almost an irrelevance. She told the historian Julie Frederikse that she was uneasy about white people’s involvement in the ANC.

In fact her opinion seemed more in line with Black Consciousness than with the ANC’s liberal approach.

‘It’s the Africans who should be in the frontline and who should be in the leadership. The fight wasn’t about getting rid of white people. The whites were just a fact of history: they were there and there was nothing much to do about them. To be honest with you, at that time I didn’t think there were enough progressive whites to make a difference. I didn’t think that all whites were bad, but I just thought there weren’t enough whites who were prepared to stick their necks out for us.’

There were two remarkable occasions when Dlamini Zuma’s management skills came to the fore. The first occurred during the UN anti-racism summit in Durban in 2001. A declaration was being drawn up, but the process had ground to a halt because of various competing interests and emotions.

Some developing countries wanted Zionism declared racist, while African and Caribbean nations wanted slavery and colonialism declared crimes against humanity, with appropriate reparations.

The Western powers would have none of it.

The conference was about to collapse, which prompted Dlamini Zuma, as a representative of the host nation, to intervene. With each crisis she would take the delegates aside and ‘force’ them to come to a compromise. Each time she managed to save the conference.

Years later, the Sunday Times journalist Mondli Makhanya would write of the conference: ‘In the end the summit adopted the Durban Declaration, which said racism and all other forms of discrimination were terrible things that good people should never practise.’

But essentially the conference’s only real meaning was to put racism on the UN’s agenda, although it also ‘exposed the highly admirable diplomatic skills and energy of Dlamini Zuma, who is one of the continent’s best political operators’. High praise from a seasoned political journalist.

WATCH: Dlamini-Zuma can lead us with dignity, say Brits residents

The second occasion occurred in Switzerland in 2004. She was part of South Africa’s high-level team bidding to host the FIFA World Cup in 2010.

Leading the group were President Thabo Mbeki and his predecessor, Nelson Mandela. Dlamini Zuma was the only woman on the team. At the time, she was foreign affairs minister and would later be closely involved in the organisation of the tournament as home affairs minister.

The story goes that on the eve of their presentation the team was confident that they would impress FIFA the next day. They were staying in a hotel in Zurich and the mood was upbeat.

Nevertheless, Dlamini Zuma gathered them in a room and wanted to know if they knew what questions they would be asked.

Sitting there were Danny Jordaan, the chief executive of the South African Football Association, soccer boss Irvin Khoza, SAFA president Molefi Oliphant and sports minister Makhenkesi Stofile.

They had anticipated some of the questions, they replied. Had they written down the questions and the answers, she asked. Not entirely.

They gave her their presentation and she suggested they reconstruct it. She went further. She had them rehearse all the answers to the anticipated questions.

When President Mbeki, and Nobel laureates Mandela, F.W. de Klerk and Archbishop Desmond Tutu joined the team in the ‘war room’, she lined them up in their respective roles and insisted on a dry run of the entire presentation. There was fierce resistance. She persisted. Finally they agreed.

A journalist reported the event in the Sunday Independent. ‘She also asked that the video presentation aimed at marketing South Africa as host be played for all in the room to view it. She then raised concerns that the video did not depict South Africa in the best possible way.

They conceded.

Assistance was sought from the SABC for additional material. The video was enhanced. And, as the rehearsals went on, the soccer bosses became more confident, like soccer players after a session with a motivational coach.’

On 15 May, a few minutes before FIFA announced the winning nation, Dlamini Zuma took care of a last concern. She didn’t want Mandela to be in the conference room where FIFA president Sepp Blatter was to make the announcement if South Africa had not won the bid. Four years previously he had been part of the team that had lost the bid for the 2006 World Cup to Germany.

She did not want him humiliated again.

She cornered a top FIFA official and learnt that it was ‘safe’ for Mandela to be present and in full view of the world when the announcement was made. There were some who believed that Dlamini Zuma, in her direction of the team, influenced their performance, which convinced FIFA of South Africa’s suitability.

Unfortunately, as with so much of her career, the FIFA achievement was tainted by subsequent revelations.

Investigative journalists found that Jordaan had sent a letter in December 2007 to FIFA where he mentioned that he had discussed a payment of $10 million to the 2010 World Cup Diaspora Legacy Programme with Dlamini Zuma and she had told him to pay the amount.

It later became apparent that this contribution to football development was intended to gain the backing of Caribbean football boss Jack Warner when it came to voting on South Africa’s bid.

Although her name was associated with this inappropriate payment, she has subsequently not been held accountable by law enforcement agencies.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners