Shweshwe – also known in Sesotho as shoeshoe for King Moshoeshoe – was once used to create simple traditional dresses, but has now become part of a fashion movement that’s modernising the use of the print.

The love of shweshwe, popularly worn in blue, brown and red, has been passed from one generation to another over centuries. It is often seen at Xhosa weddings, where it is worn by the makhoti (bride).

The streets in central Joburg’s shopping district explode with shweshwe dresses and many of the people in the area wear designs made with the fabric.

Although you’d expect an iconic material like this to boost the ailing local textile industry, producers from overseas have become aware of the revitalisation of its popularity and are flooding our market with counterfeit products.

The now distinctly African fabric has its roots in Europe. It was introduced to us by German immigrants in the mid-1800s. Locals then began using the white-patterned fabric in its rich earthy colours to make dresses and skirts.

The business of fashion

In 1992, South African textile company Da Gama in Zwelitsha, outside King William’s Town in the Eastern Cape, bought trademark rights from Tootal Fabrics in order to produce the designs locally. It made them the only original shweshwe manufacturer, not just in South Africa, but in the world.

The company imported large patterned copper rollers, used to print designs on the material, which was washed with weak acid to produce its intricate white patterns.

Da Gama Textiles has helped evolve the print over time, drawing from the talent of highly skilled artists and designers such as Lizo Somhlahlo and former designers such as Fleur Rorke (during the late 1970s), who drew inspiration for her designs from Basotho murals in Lesotho.

Helen Bester, the marketing and design manager at Da Gama, says their designs are worked on and elements changed to ensure they keep up with trends.

These days, the company registers its designs under several trademarks in each of the countries in which it trades. Each brand, including its most popular, Three Cats, can be recognised by the logo on every roll of fabric.

Copy cats

At the moment, Da Gama does most of its trading with southern Africa and a few European countries.

But this fortress of local craftsmanship is under threat from cheap imports. These sell for about half the price of the originals, which cost between R50 to R60 per metre.

China is most guilty of copying their work, says Bester. “Especially garments, which affects all designers and seamstresses in the market as they are unable to produce and sell at those low prices. They cannot survive.”

In 2013, it was estimated that Da Gama was losing 10% of its market to counterfeit polyester cotton blend shweshwe material imported from China and Pakistan. Despite this, there is a vast difference between the original and its imitations. Da Gama’s trademark shweshwe has a specific base cloth, colours, design, a 90cm width and a starchy finish. The latter was originally used to protect the fabric from damage during long journeys from Europe.

Da Gama Textiles currently has 683 employees, compared with 3 000 several years ago.

“Shweshwe is one of the company’s more profitable products and certainly plays a big role in its survival,” says Bester.

Because it is difficult to grow the market, it’s impossible for the company to employ more people.

Over the years, Da Gama has appealed to police and customs officials to eradicate the trade in counterfeit goods, but the problem has become unmanageable. They and other textile factories aren’t receiving enough support to deal with the problem.

In Nigeria, government supports the local textile industry to favour small operations that make use of very little imported fabric. This helps foster a culture of pride in local design and production.

The fabric that matters

Juliette Leeb-du Toit, the writer of the book isishweshwe: A History of the Indigenisation of Blueprint in Southern Africa, says it was an important subject for her to research and write about. This globally known fabric – a distinctive South African cloth embedded in a multifaceted historical matrix associated with trade, colonial economies, missions and cultural appropriation – represents a major historical remnant of an intercultural past, with both Pan-African, Eastern and Western dimensions. This, she says, testifies to a history of encounters and exchanges between humans across the globe.

“I felt it imperative that I share what I discovered over the years about isishweshwe, as a contribution to our collective and intertwined histories: the cloth’s significance cross-culturally, its journey from colonially imposed cloth (coupled with religion, culture and economic coercion) to its embrace as South African by its various peoples. I wanted to share what I located in museums and archives, the perceptions of those interviewed and what I located in archival documents and publications. Above all, I wanted to share the ways in which local culturally distinctive groups have elected to embrace isishweshwe and what values they attach to the cloth,” the art historian tells #Trending.

“I wanted to explore how values regarding decorum, culture, class and gender become imbricated in the wearing of the cloth largely by women, but also condoned by men. And how the cloth has acquired almost a sacredness to some users: it defines them as South Africans, as women, as bearers of deeply sensed cultural values (attached to rites of passage such as marriage and even death – in widows’ dress) and how it has become indigenised to the extent that its global heritage has become indelibly absorbed and altered, resulting in its becoming attached to a distinctive South Africanness.”

Some history

“This print has become very central to South African history, celebrated across all cultures as one of the most beloved prints. On the one hand, this is explained by traders and producers who noted that the cloth was durable, attractive and functional. These qualities testify to needs by both settler and indigenous women at various times in our history. The cloth assumed a dignity and value attached to quality and the dignity of hard work and decorum. It also testifies to women’s acute aesthetic sense and sense of design. But, over time, it has become co-opted into cultural significance, as in Lesotho where, in the 1960s, women elected to centre on this cloth in particular to define their cultural identity. Other cloth like salempore has also acquired such value in South Africa … especially among Venda women. Here it has acquired sacred connotations associated with ancestry to some,” says the author.

African couture

Says designer Maria McCloy about the printed cotton that has become synonymous with African-inspired couture: “These cloths came with colonialism, missions and traders, so I suppose Africans had no choice in those matters of who ruled them and so no choice in what materials they wore to clothe themselves as a result of their lands being taken, borders imposed, oppressive political rules and imposed religious rules and finance and shops being run by non-Africans.” Reading Leeb-du Toit’s book, one finds that many designers – probably thousands – have contributed to the shweshwe designs. The fact that it bears traces from all parts of the world makes it difficult to pinpoint the original creator of the indigo print.

“I have no idea why people so loved the cloth presented to them by colonisers and then adapted it to their tastes, as is the story with wax print’s journey into Africa, the Basotho blanket and shweshwe. These items’ designs, colours and motifs were adjusted to cater to what Africans, their market, found desirable and meaningful. In the end, the cloth and blankets became associated with African aesthetics, life, religion and ceremony,” says McCloy.

Modernisation of a classic

Another designer who, like McCloy, is at the forefront of the modernisation of shweshwe, is Shweshwekini Active Wear founder Refiloe ‘Mapitso’ Thaisi.

“As I love African prints and could not find swimwear that could fit me perfectly, I decided to create my own brand which could cater for men and women everywhere – with the comfort of wearing the pieces at the beach, in the gym and even at home,” says Thaisi.

“I think it has been remarkable to see the diverse ways in which designers have used shweshwe.

“To create yoga bags, jewellery, to decorate shoes, make hats and even bedding. It truly has transformed from a cloth that was reserved just for dresses into many artistic forms. It’s truly beautiful to see the creativity that has emerged from shweshwe. It makes me feel proud to know that I can be anywhere in world, but when I see shweshwe – for me it resembles home. It is the closest clothprint to the South African flag.”

Pan-African appreciation

While Xhosas, Sothos and Zulus are the main wearers of the cloth it has become multicultural and even Pan-African.

Leeb-du Toit says it’s difficult to ascribe its use more to one culture than to another.

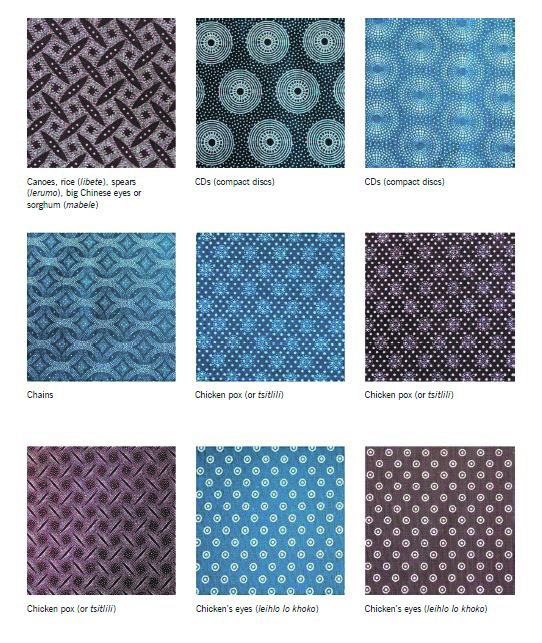

“People in Namibia use it, as did those in Zimbabwe and those in contemporary Botswana. I have located this cloth’s usage in Angola. The cloth has acquired many local names, such as ijeremani, jelman or jereman among Nguni people; motoisihi, ndoetjie and mateis in Mpumalanga and Botswana; and seshoeshoe among Sesotho speakers; and has also acquired pattern names, especially in Lesotho.”

McCloy has a Mosotho heritage and the fabric has been a part of her life because of the women in her family and her surroundings.

“It’s strongly associated with Basotho culture to me. I’m all about us wearing our heritage every day, instead of the colonial- and apartheid-induced idea that created the kind of self-hate that makes people think adorning themselves in Africanness is only for Heritage Day and weddings – so using the cloth in my shoes is very important because as much as the cloth came with colonialism, like wax cloth, this cloth now signifies and symbolises something African. In a way we made this cloth culturally significant in how we use it and the meaning attached – despite it coming from Asia and then Europe. No one thinks of that when they see the cloth. They think of Africa and in this case Lesotho or Basotho culture as a whole in southern Africa.”

- isiShweshwe: A History of the Indigenisation of Blueprint in Southern Africa is published through UKZN Press. The recommended retail price is R895

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners