Black Chronicles IV

Fada Gallery, University of Johannesburg, Bunting Road Campus, Auckland Park

Gallery hours: Tuesdays to Fridays 9am to 4pm; Saturdays 9am to 1pm; closed on public holidays

Free entrance

On my way to the exhibition opening of Black Chronicles IV, I tried obsessively to keep an open mind. The exhibition promised a range of portraits taken from the Victorian era.

My previous experiences of photographic representations of black history have always been littered with images of scantily clad bodies, held by some sort of a harness, standing next to a proud white figure. Some alternative approaches consisted of depictons of African-American slave families dressed in sub-standard attire, again denoting racial inferiority.

READ MORE: Kudzanai Chiurai's new exhibition looks at the madness of colonisation

Walking into the Fada Gallery at the University of Johannesburg, my preconceived notions began to dissipate. A brief discussion with Ama Josephine Budge, a writer, curator, artist and researcher from London, emphasised how extraordinary it is that these images exist. She dreamily described how, as a young, mixed-race girl growing up in the UK and reading Jane Austen novels, the image of a strong black woman dressed in fine clothing in this era was an almost absurd idea until she came across these images. Her words drew me to the majestic portrait of Sara Forbes Bonetta. The picture stands almost life-like, towering over all the other images in the gallery, depicting a relaxed Forbes Bonetta sporting a gentle smile. Come to think of it, hers is one of the few pictures where a modest smile can be detected.

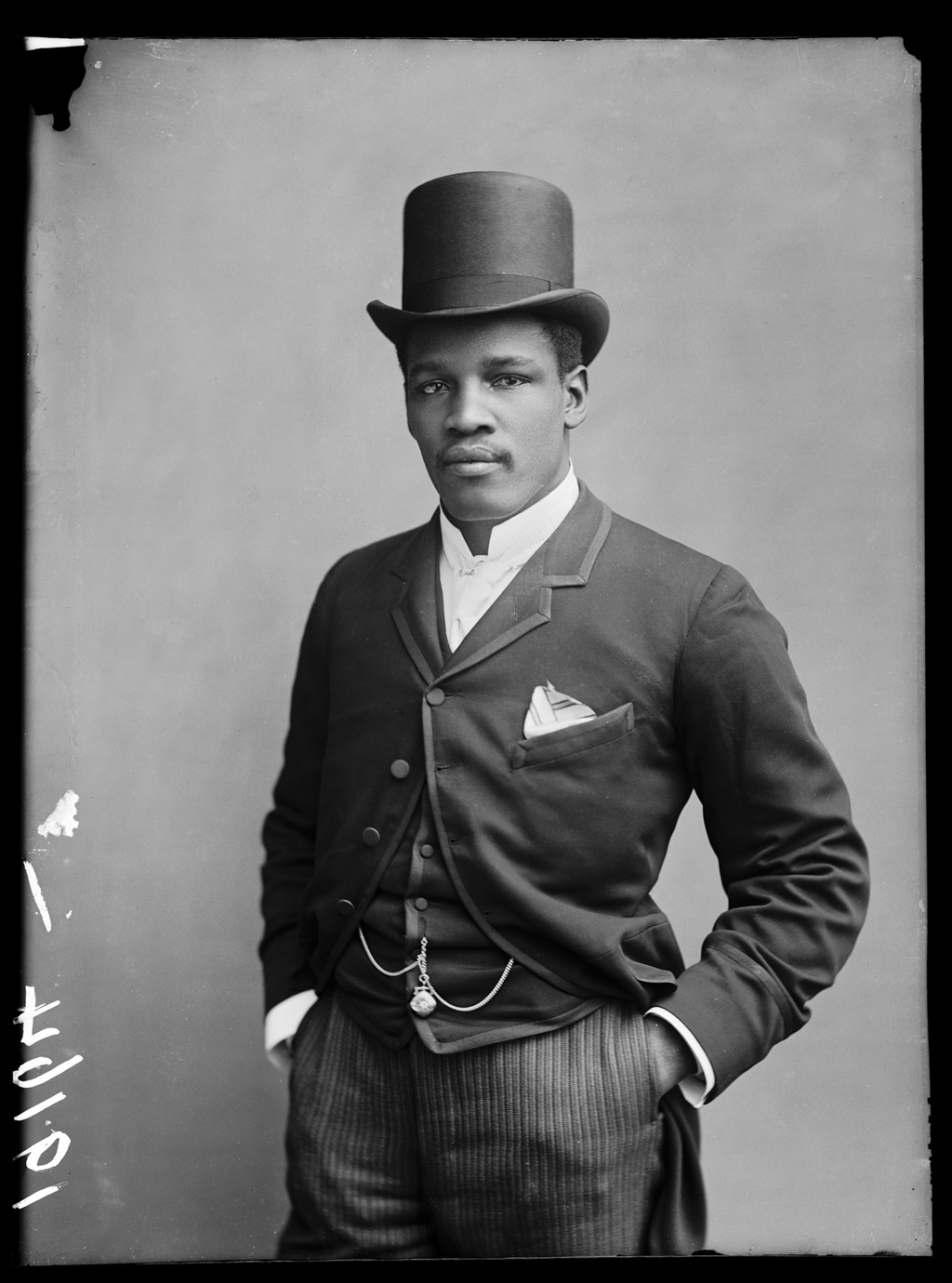

A slight turn of the eye away from Forbes Bonetta, one is met with three panels showing a young, distinguished gentleman standing in a strong, assertive pose. He is Peter Jackson, a boxer originally from what is now known as the US Virgin Islands. Jackson would subsequently gain Australian citizenship, and his career took him to the US and later the UK. I shudder at the thought of the struggle of a black boxer in 1890’s Europe; my only consolation came from how indestructible he looks in these images. If I were to inherit that sort of strife, I would want to look like he does.

READ MORE: This Kenyan artist imagines the Masai in space

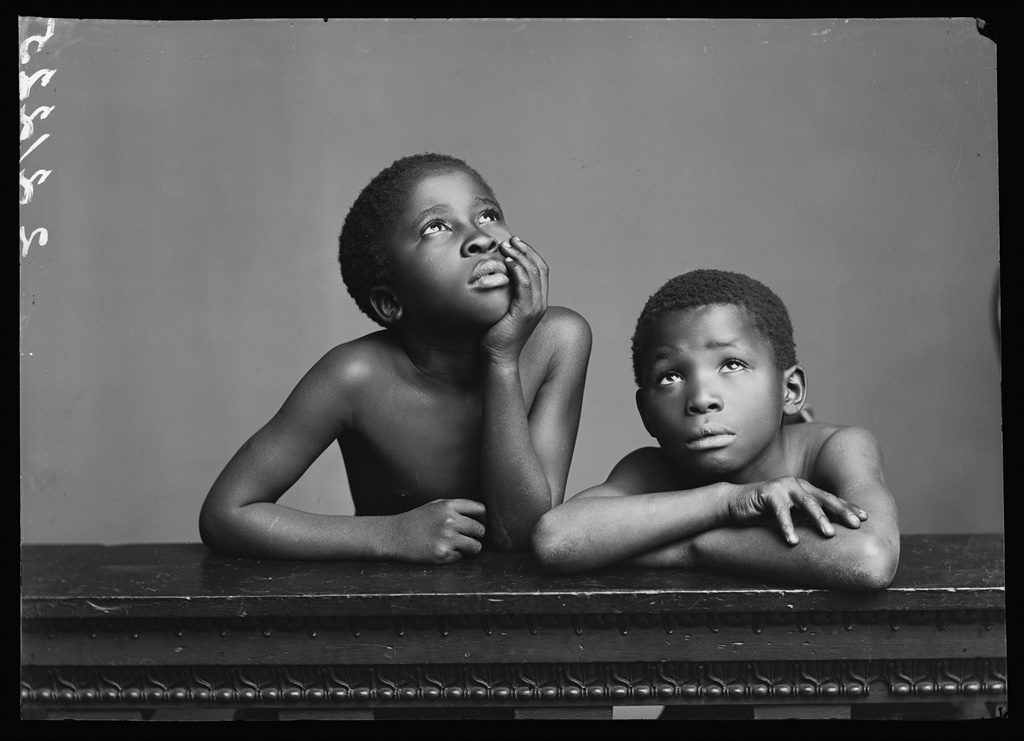

My attention shifts to the two panels beside Jackson’s. A young boy, barely a teenager – his innocence clearly visible. Kalulu was a slave who was later adopted by Henry Morton Stanley. Yes, the same Henry Morton Stanley who uttered the words “Dr Livingstone, I presume?”

Kalulu’s pictures are displayed in stark contrast to Jackson’s. I gravitate towards the one in which he is wrapped in a shawl, standing in a stoic, almost feminine pose. For a second, I’m taken aback by the sheer quality of these pictures – photography was such a young technology at this time.

The true gem of this exhibition lies in the sound- and image-based installation of The African Choir. The group of South African singers, including Charlotte Maxeke and Eleanor Xiniwe, toured the UK, even performing for Queen Victoria, in the early 1890s to raise funds to build a technical college in South Africa. The installation includes a five-track

reimagining of the choir’s 19th-century concert programme. To my surprise, a physical copy of the programme is also there for one to view, along with a newspaper article that gives detailed information on some of the key members of the choir.

READ MORE: The authentic eye of photographer Mário Macilau

Racial inequality and race relations are a continuous battle even in the 21st century, and what this exhibition has afforded me is a keyhole view of a lost piece of black history ... lost for a 125 odd years.

Renée Mussai, senior curator and head of archive and research at Autograph ABP, describes it best when she states that “At the heart of the exhibition is the desire to resurrect black figures from oblivion and reintroduce them into contemporary consciousness.”

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners