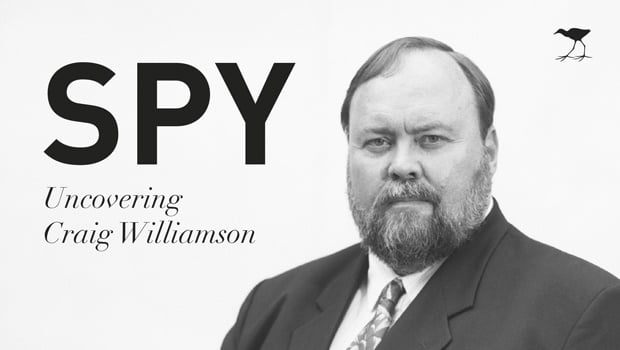

About the book:

It was in 1972 when the seemingly ordinary Craig Williamson registered at Wits University and joined the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). Williamson was elected NUSAS’s vice president and in January 1977, when his career in student politics came to an abrupt end, he fled the country and from Europe continued his anti-apartheid ‘work’.

But Williamson was not the activist his friends and comrades thought he was. In January 1980, Captain Williamson was unmasked as a South African spy.

Williamson returned to South Africa and during the turbulent 1980s worked for the foreign section of the South African Police’s notorious Security Branch and South Africa’s ‘super-spy’ transformed into a parcel-bomb assassin.

This excerpt from SPY: Uncovering Craig Williamson was published with permission from Jacana Media and is available from all leading book stores.

Chapter 16

Craig Williamson led a double life, infiltrating NUSAS, the white left, the anti-apartheid community in exile and, to some degree, the ANC. His infiltration strategy involved befriending, gaining trust and betraying.

South Africa’s struggle for liberation was plagued with acts of betrayal. Jacob Dlamini’s book Askari documents how captured MK soldiers were beaten and tortured by the police to get them to turn against their comrades.

In Stones against the Mirror, Hugh Lewin writes about how his best friend, Adrian Leftwich, betrayed him by turning state witness to save his own skin when both were arrested on charges of sabotage. Williamson’s betrayal was different; he wasn’t a friend and comrade who started out on the same side and was ‘turned’ by force.

Without any compulsion, he chose to become a spy.

To be a good spy you need to become a trusted member of the inner circle of the group you’re targeting. You have to get close to the people you are spying on. Your false identity has to be real. Successful spies form genuine friendships and allegiances – and that’s just what Williamson did when he arrived on Wits campus in 1972.

He contrived friendships, manipulated trust and manufactured an image for himself as a leftist fighting against apartheid.

Spies betray on at least two levels. The first is their assumed loyalty to the cause of the group they have infiltrated; in Williamson’s case, the South African liberation struggle. The other is a personal betrayal, because a spy lies and deceives people who believe him to be their friend and on their side.

The pain of betrayal is magnified by a sense of vulnerability, because the deceitful conduct shatters the worldview of the person who has been betrayed.

When activists are able to maintain the illusion that the enemy is on the other side, they create a psychological safe space, but when it turns out that the enemy is actually inside their circle, they feel exposed and angry.

This is why some of Williamson’s former NUSAS comrades were reluctant to speak to me. ‘I thought we’d buried that ghost a long time ago,’ said one. ‘Williamson takes enormous pleasure in prominence and publicity; his best punishment is to play him down,’ said another.

Nearly a quarter of a century after the country’s first democratic election in 1994, former enemies have reconciled and many people who committed terrible atrocities have been forgiven by their victims and their victims’ families.

However, a lot of bitterness is still directed at former spies.

A storm of outrage broke out in 2015 when Olivia Forsyth, who had been recruited as a spy by Williamson in 1980 and infiltrated the Rhodes University chapter of NUSAS, promoted her memoir, Agent 407: A South African Spy Breaks Her Silence.

People she had betrayed called on readers to boycott the book and disrupt any launches. One former Rhodes student even suggested shaving her head and parading her down the streets of Grahamstown, a punishment meted out to French women who collaborated with the Nazis.

The scars of betrayal do not heal easily. When Williamson was unmasked, some of the people he had deceived felt vindicated, a few were surprised, but most were furious.

Glenn Moss, who worked with Williamson on the Wits SRC and in NUSAS:

I didn’t have a sense of personal betrayal and I wasn’t morally offended that Williamson betrayed me.

We were involved in a political struggle and there were people on different sides. He was sent in to infiltrate us and he did his job, which was to inform on us. Our job was to limit the damage the spies did by informing.

Cedric de Beer, fellow St John’s College pupil and NUSAS activist convinced to the point of obsession that Williamson was a spy:

When I heard he was exposed, I felt a sense of relief.

Charles Nupen, former NUSAS president who worked with Williamson:

I might have described him as a friend, maybe not as a close friend, but a friend. Particularly when I was on trial in Johannesburg, my wife was in Cape Town on her own. He was in Cape Town and reached out to her, phoning her to ask her how she was doing, and he and Ingrid took her out for dinner every so often.

It was part of the façade of deceit, the constant need to ingratiate yourself in a way with those who you were spying on – and who could potentially be a source of information.

I don’t want to psychoanalyse this man: he is obviously a fraught and complicated individual, but I see him as a person who, at all times, used people instrumentally. To be able to do what he did – live a life that he did – I’d imagine that there would be pretty strong psychopathic tendencies.

Gerry Maré, former NUSAS activist:

One night, after a party in Hout Bay, I was riding my motorbike home when I noticed Williamson and Ingrid, who had left the party at the same time as me, driving behind me. He drove so close behind me.

We went over Constantia Nek, a narrow, twisty pass with no shoulders. When you are on a motorbike and a car behind you gets too close, you move over or overtake the car in front of you, but you get away from the car.

However, there was nowhere for me to go. I knew that if I came off the motorbike, that would be the end of me. I crapped myself on that trip home, but had to stay calm. It was only when I heard that Williamson was a spy and he was working for the other side that I thought that maybe he was actually trying to kill me.

Julian Sturgeon, former student activist, who became Williamson’s ‘assistant’ in exile:

Even though there were signs that he wasn’t what he made himself out to be, it still came as a shock when he was exposed. I had to go through my dealings with him to see just how badly I’d been duped.

It was a betrayal, but I also felt like a complete moron that I had allowed myself to be duped. I realised so many things that I missed, which made sense… in retrospect. I remember Craig shedding crocodile tears when he told me that [Black Consciousness activist] Mapetla Mohapi was murdered by the security police in detention in August 1976.

I remember him saying what a terrible blow it was because Mapetla was such a potent guy. Of course, it was all bullshit.

Because I had worked closely with Williamson, I was fingered as an agent and the ANC shunned me. White South African lefties would cross the street rather than talk to me.

Tad Matsui, World University Service representative in Switzerland and ‘friend’ of Williamson:

I was back in Canada, working for the Canadian Council of Churches, when Craig was exposed. I was devastated. There are two things that devastated me about my work with South Africa. One is the death of Steve Biko and the other was the exposure of Williamson.

Richard Taylor, general secretary of WUS in Geneva, phoned to ask me for all the names of the people I introduced to Craig. The Canadian government didn’t like me after that – they had supported IUEF and they didn’t distinguish between WUS and IUEF. I kept trying to explain that we were different; we were a student-run organisation, we’re democratic. The worst part of my dealing with Craig is that after he was exposed I became suspicious of all white South Africans.

WATCH: Here's why former apartheid spy, Olivia Forsyth became a double agent

Interested in reading the book? Purchase a copy of SPY from Takealot.com.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners