A Joburg Monday afternoon and the weather is transitioning, winter nudging summer aside, watering down the sun. Lebo Mashile arrives bearing take-aways from Fordsburg, delicious curries and naan breads. She has just arrived from Cape Town, where the first iteration of her stage play Saartjie vs Venus was greeted with critical acclaim at Design Indaba.

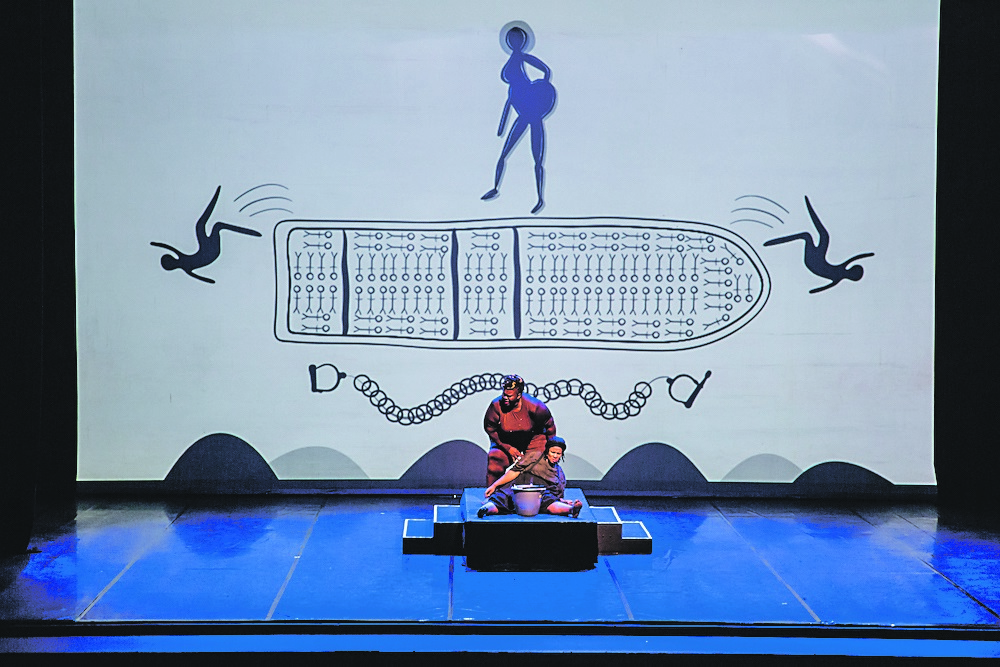

The play – featuring Mashile as Saartjie and opera star Ann Masina as Venus, both fuller-figured women – has been brewing in Mashile’s world for decades.

When, apart from your entire life, do you recall becoming conscientised about Saartjie?

I first became conscious of Saartjie at 21, when I was studying at Wits. And then, years later, I was suffering, sah-fah-ring [laughs], after my big ascent and burnout. You know, like, 12 countries and two books in three years. And in that space she came back to me again in the form of Rachel Holmes’ book, her biography, which is really detailed and helped me understand how Saartjie defined herself as a performer.

READ MORE: Why you should fall in love with poetry

Aside from and despite the harrowing circumstances she had to endure, the oppression that, God, had enveloped the whole of the planet and black people, here was a woman who said: ‘I’m going to get on to a boat and go to the UK and be famous!’

We weren’t taught the proper history. Please educate us ...

Saartjie grew up in Gamtoos River Valley, a community whose life had been interrupted by colonialism. Her father was kind of like a trader-trapper, cowboy-type of person who would go out on long expeditions and would interact with these people who were on the frontier of black and white life colliding.

She lost her mother when she was very young. She was raised by her siblings and, at the age of 16, these raiders come into her community one night and destroyed everything. She’s taken to Cape Town as an indentured servant. So, one of the big stories we want to tell in this piece is the story of Cape Town as a slave port. She had a life in Cape Town at the slave lodge. She had two children in Cape Town.

So two years ago, when I started intensely researching this piece, when she came back to me again [yells the word], after having done Pamela Nomvete’s stage adaptation of her life, Ngiyadansa. Pam would go on to direct Saartjie vs Venus because in her work, she’s always complicating black women’s lives, taking one black woman and making her multiple characters, to see different aspects of her identity and who she is and how women make choices.

I saw the precursor for the piece when you performed Venus Hottentot vs Modernity with the divine Ann Masina at The Centre for the Less Good Idea

Yes. That’s where I met Ann. She’s Venus and I’m Saartjie. So she plays the spirit, the divine feminine, the enduring, the eternal force that comes out on stage. When Saartjie leaves Cape Town, Venus is literally the ship, the middle passage, all the spirits. There are so many aspects of my life and Ann’s life that intersect with Saartjie’s, you know?

Being on stage, being black women moving through space, having to deal with, no matter how, or how you choose to present yourself, always being reduced to whatever someone else’s perception of your body is. Hypersexualisation and still being devalued at the same time; being super-visible but still being erased!

READ MORE: I changed 3 bad habits after following these body positive bloggers

Back to the story ...

The Slave Lodge in Cape Town was where the Dutch East India Company kept their 800 slaves. They were the biggest multinational conglomerate in town. If you wanted any kind of skilled tradesman or craftsman, you would go there by day. By night, if you are a white man who has money, you can go there and sleep with whomever you want: man, woman or child. For a Khoi woman coming into contact with, live and direct, the coalface of white supremacy – that would have been hell!

Of course, somebody comes offering you fame and fortune at a time when black bodies are crisscrossing the sea as slaves, and you’re being sold to the concept of fame? I would choose that. She chose to leave and go to the UK. And then was put on display at Piccadilly Circus. She was taken to the UK by a man who she was already working for here in Cape Town.

A guy called [Hendrik] Cesars. Some accounts say he could’ve been mixed-race himself, which further complicates the story of slavery, right? So, they get to Europe and obviously fame is not what fame has been sold to her as. At the peak of her fame, she was doing 12 shows a day for this guy and still going home and cooking and cleaning for him.

But she was basically a pop star?

She was on the cover of everything. You know, she was the equivalent of Brenda, Beyoncé, was a reference for fashion designers, changed fashion! People started adding those corset underthings that could make your bum look big as a direct response to this woman’s visibility. She was a reference for political satirists, cartoonists. So here’s this woman who is the hottest act in town, who’s completely voiceless, powerless.

At some stage the abolitionists get involved and raise questions around how she got into the country. And during the course of the trial, she says: ‘I am artist, I am not a slave ... I don’t want to go back to South Africa. I’m not done here; I still need to make money here.’ So those are very powerful choices. That’s what I wanted to examine. What is a slave? And what is the line between fame and slavery; sex work and performance art; hypervisibility and invisibility? And how do you choose to position yourself, because fame is that constant negotiation of selling yourself. I’m always negotiating, whether I like it or not, people’s perception of me.

At my most empowered I choose to deliberately f**k with it. But I’m also at its mercy; that’s what feeds my kids. And no one is spared. Beyoncé is not spared; Brenda is not spared; Miriam was not spared; Tina Turner was not spared. I’m not spared and Ann is not spared. Why does putting your sexuality first somehow compromise your intellect? Why does it compromise your ability to be taken seriously? Josephine Baker ... Every model of black woman superstardom that we have, has an intersecting point with Saartjie.

READ MORE: 5 bloggers who teach us the importance of self-love

What was Saartjie’s art about?

She would sing, she designed her costumes, she had a body stocking – people said that she was displayed naked, but she had a flesh-coloured body stocking. She had beaded regalia, she had a cape. I mean, she stepped into a persona on stage. She made a decision to assume a character. And she played indigenous instruments, she sang indigenous songs, she danced. Yet she was labelled a freak.

You can stand up there reciting Shakespeare and, if people have paid five pounds to touch your ass, they’re gonna touch your ass. After she died at the age of 25 they made a life-size cast of her body, which was presented at seminars and scientific doctoral presentations for years and years. Then they took her skull, her skeleton and preserved it, and then took her vagina and her brain and preserved them. And those were placed on display. So ultimately people didn’t know to engage with the beauty that she was presenting. And this is what happens when you have white supremacists, when you have sexist people, documenting the stories of black people, of black women.

The beauty of what you’re doing, the complexity of what you’re doing, the true story that you’re telling gets completely erased – we all become freaks. If my story is left up to white supremacy, I’ll be a freak too.

- Mashile is developing Saartjie vs Venus from a 45-minute work into a full-length production likely to premiere later this year

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners