How an African languages project seeks to create platform to bring previously marginalised indigenous languages to the forefront of teaching and learning at higher institutions, writes Rethabile Possa-Mogoera

For many years black students have been disadvantaged, especially those who are from rural and township schools when they finally transfer to colleges and universities.

It is a fact that unlike in English-medium schools, the English language is not a priority at township and rural schools. Inevitably, when they move into tertiary institutions - especially formerly white universities like the University of Cape Town (UCT) where the majority of students are privileged - these students are bound to struggle to keep up.

These students struggle, not because they do not know what is being taught or the concepts presented – but because English is the only medium of instruction.

This is one of the reasons we have more black students dropping out at UCT and other previously advantaged universities than white students.

READ: Rhodes, UCT partner to decolonise historical archives

If these students could be given an opportunity to learn or express themselves in their indigenous languages, these struggles would be ameliorated.

This is the reason why I am advocating for decolonizing the curriculum by taking UCT to task and publishing our indigenous language material that will be used in teaching and learning.

After I published one of my Sesotho drama books, I did not stop but rather sent out a call to my colleagues at other South African universities and neighbouring countries like Lesotho and Eswatini to write chapters in indigenous languages in a way of creating content that will be used to teach at higher institutions of learning.

The reception was amazing.

Contributors included an occupational therapist, linguists, and language experts.

I received funding from the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS) to do this project. Though the money was not a lot, I believe when funders realise that our indigenous languages can be used at institutions of higher learning, they will fund more projects of this nature.

The project

This project stems from the fact that scholarly work on Sesotho as a language, published in Sesotho, is very limited to non-existent in South Africa and Lesotho where the language is an official language.

Some Sesotho texts used in higher education are outdated, e.g. Jacotte, (1927), Jankie (1939), Doke & Mofokeng, (1957), and Guma (1971). One such seminal text was developed and written by the missionaries, Jaccote and Jankie in the 1800s. Lekhotla la Sesotho (Sesotho academy) was then established to further develop the Sesotho language in Lesotho.

However, when the academy developed Sebopeho-Puo (1994), the main text used for the teaching of the linguistic components of Sesotho, the academy simply adopted the structure proposed by the missionaries without further development.

READ: Let’s introduce liberal arts at basic education level

In South Africa, Swanepoel and Lenake (1979) produced Mathe le leleme 1 & 2, which has remained the primary text used in the teaching of Sesotho.

Sesotho, like other languages in the world, has undergone linguistic changes, due to among others globalization which has resulted in increased contact between languages.

In addition, developments in the fields of science, technology, and culture, have also influenced changes in languages due to the constant need for languages to create new terms to name and describe new concepts. Words are also borrowed in various situations where two or more cultures coexist and begin to influence each other within the broader society.

For South Africa and Lesotho, Sesotho has changed predominantly due to contact with other African languages, which are genetically related, as well as with English and Afrikaans, which are typologically related. However, not much progress is evident in Sesotho literature, although notable changes are present in spoken Sesotho.

This poses a challenge to both lecturers and students as the English texts are based on theories informed by English culture which is considerably different from the Sesotho culture. This slows down the intellectualization of Sesotho as a language of education and research in the higher education context.

Recent publications produced about Sesotho language are published in English (Possa (2015), Seema (2016), Rapeane-Mathonsi (2011), Phindane (2019), Mokala, 2020) which adds to the stagnation of the Sesotho language.

Although research is often conducted in Sesotho, for publishing purposes, the work is translated into English and literature supports the notion that meaning is often lost in translation (Mohlomi, 2010).

Translation from English to Sesotho greatly impacts the language and its development. This translation also shows that Sesotho is not yet recognized as a scientific language that can be used for publishing purposes.

READ: Dashiki | Uthini? Bua, morena. Andikuva tu!

For the status and use of Sesotho to be improved, the language needs to be developed through research and production of literature in Sesotho.

Progress

I am sitting with two completed monographs of about 30 chapters from academics waiting for UCT Libraries that is going to publish these works. This is a multidisciplinary project that cuts across areas such as history, law, health, linguistics and literature, and this shows that it is possible to decolonise the curriculum.

Conference

I went to the World Federation of Occupational Therapist Conference in Paris end of August where I advocated for decolonising the curriculum. At this conference I argued that in Africa, texts used for teaching of occupational therapy are predominantly in English, despite majority of service users are speaking a home language other than English.

For South Africa, where the majority of the population speaks African indigenous languages, it would be assumed that occupational therapists are equipped with linguistic skills necessary for working with this population.

However, that is not the case.

The challenge experienced by educators who desire to include indigenous languages in teaching, is that there is limited to no material in these languages due to poor efforts of intellectualizing them.

This does not happen in occupational therapy only but in other fields as well.

New project

My colleagues and I from our African Languages and Literature Department are embarking on writing chapters in IsiXhosa using their teaching experience in the faculty of Health Sciences where the use of indigenous languages is key, especially for medical doctors and therapists.

This project will also help students to be equipped with not just the language but also alleviate challenges that they face when they leave varsity. I hope to see more projects of this nation in other African Languages and Literature too.

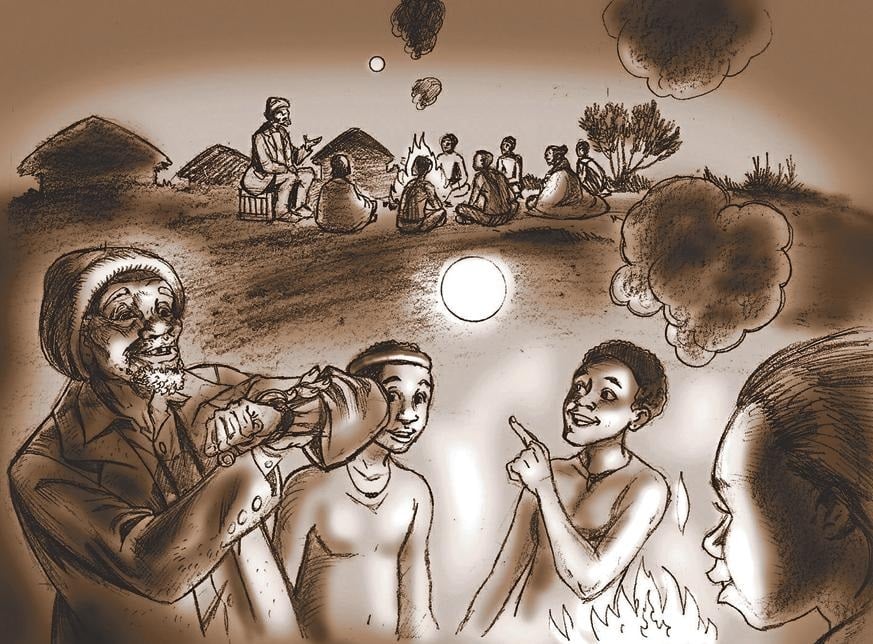

Ngugi wa Thiong'o concludes that it is very important to normalise the culture of teaching and learning African languages. We have already seen how colonialism works; they force their own language/self-knowledge on us and devalue our languages ?? and culture.

READ: African languages at schools still essential

By doing so they make it seem like their language is classy and everyone who learns it hates the languages of the black people. Language is exactly what carries values in the way people live at a certain time.

We need to build our local languages. It is only in colonialism that black people's languages ?? are suppressed.

Learning our languages is important for our knowledge.

Dr Rethabile Possa-Mogoera is a Senior lecturer and Head of Section at the School of Languages and Literatures, University of Cape Town

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners