Large dark clouds cast shadows over the mountain. It was 10:00 in the morning, but it looked like night-time. I was forced to use my headlamp for the first time to make out anything inside the tent. It was 20 January. Winter had arrived.

*****

The southern wind was blowing in just the right direction, unlike the day before.

It was still as strong as ever, but I didn’t waste any more time worrying about kite size and manoeuvrability. I took off, moving full speed ahead in the wake of my red-and-white, ten-square-metre sail.

I dropped in altitude and picked up even more speed. The ice in front of me was slashed with cracks and sastrugi, and barriers rose up before me like genuine waves of ice.

I felt like I was navigating the Roaring Forties, except that if I attempted to mess around with one of those breakers, my time would be up.

After two hours of high-speed skiing, that’s exactly what happened. I barely avoided a pitfall, then leaned into the edges of my skis like someone possessed to avoid another pitfall.

The third, however, sent me flying. I crash-landed on my arse. My neck was bruised and my ankle half twisted, but in the heat of the moment I didn’t feel the pain. I was only aware of my willpower, spurring me on to get out of there as quickly as possible.

To be safe, I took the time to change my sail. I decided on the next smaller size: the six-square-metre kite, a pink cloud in a crystal-clear sky. At the speed I was travelling, the cold stung my cheeks, despite the beard that I was now sporting, worthy of an orthodox priest.

The descent was becoming increasingly pronounced and my sled, which now weighed about one hundred and ninety kilograms, caught up with me every now and then, forcing me to take ever more risks by accelerating. It turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

I was moving at a speed of about forty kilometres an hour when, somewhere around the 160th kilometre, the ice gave way under my blades: an enormous crevasse, a chasm about fifty metres wide.

I had only about a quarter of a second to react, to gather all my strength into my biceps, to pull on my kite like a windlass, to close my eyes and fly over the snow bridge despite the 256 kilograms of gear behind me. I had never experienced anything like it. I didn’t know it was possible to glide with angels above the void. It was the first time I had ever kite-skied in such extreme – and exhilarating – conditions.

Twenty kilometres later, the gaping jaws of a second crevasse, almost as impressive as the first, stretched before me. This time, I didn’t think twice. I flew over it like the first, at full tilt.

Those fractures in the ice could only mean one thing: the first foothills of Dome C were within reach. I had been on my skis for almost thirteen hours. I decided to stop then and there, but only to switch to an even smaller sail.

The wind had picked up and I was still raring to go, determined to pass the 200-kilometre mark that day. I used what little lucidity I had left to pick out oncoming crevasses, and two hours later, a sastruga sent my sled flying again.

I managed to avoid falling, but the tarp of my sled was slashed lengthwise. It was a metrelong tear. I didn’t want to lose what remained of my equipment and decided to pitch my tent right there. That night I slept like a log.

**

The following day the wind was still blowing strong at about sixty kilometres an hour. The sound of those roaring winds was the first thing I heard that day. My tent crouched low between its fibreglass poles, as if burrowing into the ice.

This particular model had been put to test in a wind tunnel to ensure it wouldn’t be blown away even by the most extreme wind conditions. Its aerodynamic design was inspired by Formula One fins that stabilise cars speeding at over three hundred kilometres an hour.

The blizzard could roar in my ears all it wanted. It cheered me up, in fact. It was the first song I heard every morning, and was the music that filled my days, apart from what I listened to when I put on my headphones.

**

Although the next day was identical to the one before, I now had to make it across the final stretch of the long descent from the South Pole. And yet, there were more of the same sastrugi and the same crevasses, in increasing numbers.

I decided to match my performance of the day before. Maybe I could even be a little more aggressive.

Before I took on the first slopes of the glacier, I wanted to put as much room as possible between myself and the oncoming winter. So I deliberately supersized my kite and knocked off over two hundred kilometres in the wake of my supersonic 12-square-metre kite.

By the end of that day, I felt as if I had the arms of a strongman. I had harness-pared hips and a pounding heart, but it didn’t feel as if I had much of a grip on anything.

I had been trekking for nearly fourteen hours, and on several occasions I considered stopping to reduce my sail size, but ice peaks kept springing up all over the place. I didn’t want to risk a wrong move, which would have meant another long session of detangling.

Soon I had the 80th parallel in my sights. It was a small victory and a symbol of nearing the South Pole, which has a latitude of 90 degrees south.

That night in my tent, I cheered myself on. That’s right, Mike. You’re on the right track, now. You’ll soon be home safe and sound.

**

On every day of my journey, I had felt that the hard part was about to begin. That’s what I thought to myself as I was setting up camp 12 hours later, almost 3 600 kilometres away from where the nesting penguins had summoned me to dock.

I had been travelling for 40 days already. How many did I have left to go? I was midway through the second half of the expedition.

Is the glass half empty or half full? I immediately nipped that thought in the bud. I was not supposed to think like that. That wasn’t me. The glass is what it is, period.

I could calculate the numbers in every which way, but they were not going to beam me to the other side of the mountain. The key was to beat the cold, the exhaustion, the snowdrifts and the crevasses, all the obstacles which, piled on top of one another, seem insurmountable.

If I had negative thoughts every time I was about to set foot on the edge of a precipice, I would never make it.

When I made the ascent, I needed to visualise the incline as if it were as flat as the palm of my hand. I had to climb with my head as much as with my battered legs. I knew how to do it: I moved forwards one metre, and then I would tell myself: why not ten? And then, why not 100? ‘Why not’ was the secret.

I was hurting all over: by now, that feeling had become the norm. I didn’t often take my shirt off, but when I did it that morning, I noticed that I had probably lost around ten kilograms.

And yet, I wasn’t going hungry. The truth was that I had never felt as capable as I had felt during those last few days. My muscles were strained and riddled with cramps, but they always responded promptly when it came to pushing myself ahead like a galley slave. I hadn’t given up on my agonising feet either.

They were still holding me up, after all. In the morning, I would put on my boots while gritting my teeth, but on they went. And we would set off, nice and easy, just me and my old clodhoppers.

But not that day. I decided that I was not going anywhere. The blue sky that had accompanied me thus far had given way to a steely grey cover of clouds, concealing the sun.

Large dark clouds cast shadows over the mountain. It was 10:00 in the morning, but it looked like night-time. I was forced to use my headlamp for the first time to make out anything inside the tent. It was 20 January. Winter had arrived.

The wind was keeping a low profile in the face of the abrupt change.

For the sake of appearances, I tried to get my biggest kite off the ground. No go. I walked for an hour or two, my sled in tow; I didn’t want to sit idly in my tent.

Before long, however, it was clear to me that no matter how I tried to bend my body to my will, I needed to rest a little. Nevertheless, I decided not to stow away my kite in the sled: instead, I anchored it to the ice, with the lines stretched taut and ready for use. If I had to, I could be off in the blink of an eye.

I love that resolve that orders me to keep going while nature commands me to rest. I never make excuses and run away from a fight.

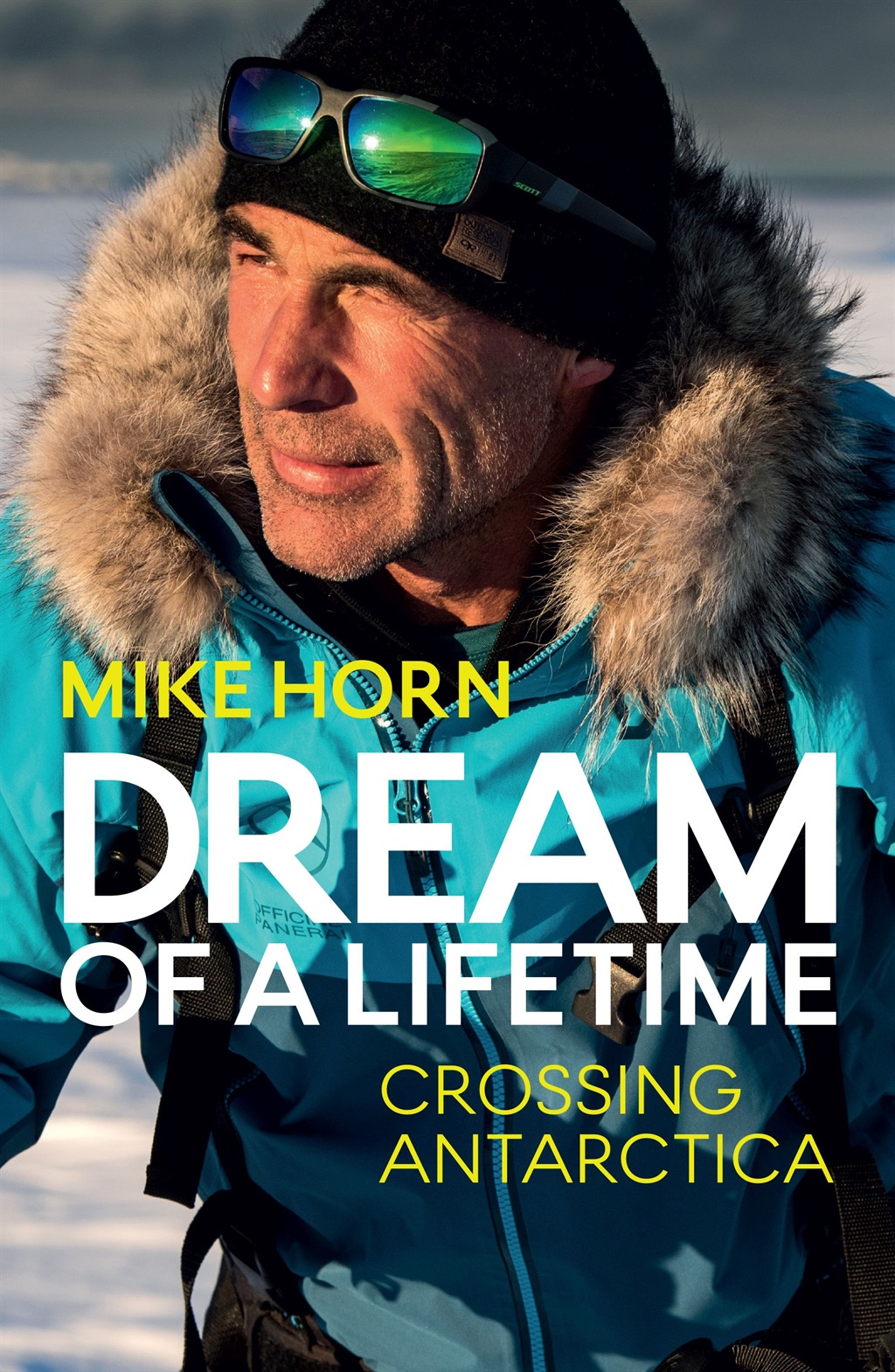

This is an extract from Dream of a Lifetime: Crossing Antarctica by Mike Horn and is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners