He’s been buying at £3 100 (R63 550) and selling for £10 000 (R205 000), Omar Aziz tells us as he rushes between business meetings in London. The 23-year-old isn’t talking about stocks, but the mark-up on Generation Z’s new favourite asset class: trainers. Dior x Nike Air Jordan 1 Highs, to be precise.

Omar has just opened a shop in Knightsbridge, one of London’s most sought-after postcodes, where he sells limited-edition trainers to a customer base that includes famous rappers and wealthy expats. Standing across from Harrods, the store has the kind of opulent decor and trendy name you might expect. It’s called “CONCEPT”, but without the vowels. Omar’s business partner, 27-year-old David Lemos, welcomes me into the store.

Each shoe has been individually vacuum-packed in see-through plastic and carefully arranged on white marble pedestals. There is a line of fur jackets hanging from gold railings, two tall mannequins dressed in floor-length ballgowns, white leather armchairs and a wall of diamond rings, gold necklaces and marble-sized pearls.

For the two entrepreneurs, trainers – or sneakers, as some people call them – are assets.

“I’d rather put my money in shoes than bitcoin,” Omar says.

They are part of a growing community of traders who buy limited-edition, difficult-to-source trainers from brands including Nike and Adidas, and luxury labels such as Chanel, then resell them – marked up – to “sneakerheads”, trainer lovers willing to spend hundreds or thousands on shoes.

In a recent report, the US investment bank Cowen concluded that sneakers were emerging as an alternative asset class. On rare occasions they can even cost in the millions.

In October a pair of old trainers worn by the basketball legend Michael Jordan were sold at the auction house Sotheby’s for $1,5 million (R22,5 million). And in a private sale in April, Sotheby’s sold a pair of Nike Air Yeezy 1s for a record-breaking $1,8 million (R27 million).

The trainers were a prototype, the first collaboration between Nike and the rapper Kanye West, who went on to build a billion-dollar brand, first with Nike, then Adidas. That’s why they were snapped up for such an exorbitant sum – they’re a part of sneaker history. They were bought by the finance start-up Rares, which plans to sell shares in them.

Expensive trainers and a receptive consumer base are nothing new. A careful blend of marketing, artificial scarcity and celebrity backing helped transform the humble sports shoe into a cult product.

But demand for sneakers has expanded particularly rapidly over the past few years. Specialised online marketplaces have reduced the risk of counterfeits with authentication services, causing prices and consumer hysteria to rocket. When a new trainer hits the shops – or “drops” – everyone wants a pair. And when there’s a limited supply, that creates a booming aftermarket.

The trainer resale sector grew by $4 billion (R60 billion) in the two years to 2021, according to US bank Piper Sandler; Cowen estimates it has the “potential to reach” $30 billion (R450 billion) by 2030.

“Since the lockdown started we’ve had hundreds of thousands of first-time sellers,” says Olivier Van Calster at StockX, the world’s largest trainer reselling marketplace. “At the start of the pandemic we saw a few weeks of real slowdown as people were asking themselves, ‘What’s happening here?’, but very quickly we saw a bounce-back and an incredible acceleration.”

With little to spend their money on while shops were closed, youngsters turned to virtual sneaker marketplaces to try their hand at trainer trading. StockX, which also handles other collectables such as clothes and electronics, says it has an average of 30 million website visitors a month. It earns fees from every sale and was valued at $3,8 billion (R57 billion) in a fundraising round this year.

Buying habits on the StockX platform suggest that people are increasingly treating sneakers as an investment opportunity rather than a personal item of footwear. Typical users will purchase at least three identical pairs, Van Calster says. “One to keep because they know it’s going to appreciate in price, one to wear because it’s a cool product, and a third pair that they’ll sell in the short term to pay for the other two.”

JOIN THE YOU BOOK CLUB | Sign up for our free weekly books newsletter and get access to reviews, author interviews, book extracts and giveaways

The sneaker market is soaring. And it is young, scrappy entrepreneurs who look set to profit.

“In the 1970s,” says the trainer historian Sean Williams, “if you wore sneakers you were seen as someone with no ambition who wouldn’t achieve much. People might assume you were a criminal.”

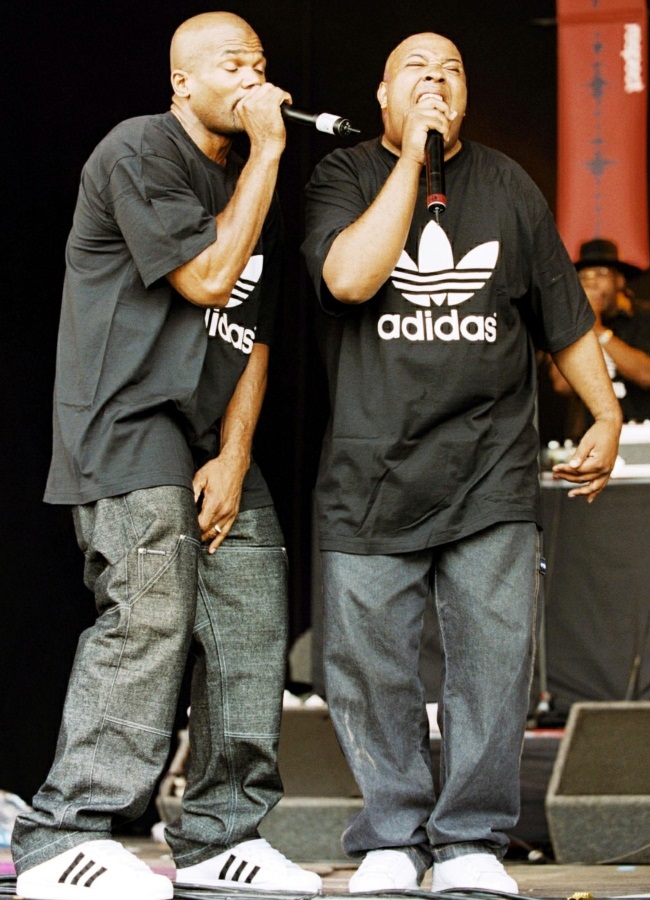

The negative connotations attracted emerging hip-hop artists, whose music challenged the stereotypes.

“As a youth-based anti-establishment movement, sneakers were perfect as an official part of [hip-hop],” Williams adds. “They were a uniform.”

Trainers became a way of signalling you belonged to this emerging youth culture – and brands were catching on. In 1986 Adidas sponsored the US hip-hop band Run-DMC in a $1 million (R2,3 million) endorsement deal after the group released a single called My Adidas, an ode to their trademark footwear, Adidas Superstars.

The collaboration established sneakers as a non-athletic, everyday shoe for the first time. Around the same time as hip-hop was emerging, another event was taking place in the world of basketball that helped solidify the sneaker’s new-found status. In 1985 Michael Jordan was in dispute with the NBA. He had been banned from wearing a pair of black and red Nike shoes on court because they violated a rule that stipulated trainers had to be at least 51 per cent white. Jordan wore them anyway and was fined $5 000 for each game he played.

Many were outraged to see the superstar being told what to do – and some saw it as symbolic of a wider issue involving race in basketball.

“A lot of people took it as a connotation,” Williams says. “They said, ‘Well, what’s wrong with all-black shoes?’ ”

It was a big coup for Nike. Later that year the brand began marketing the Air Jordan 1 as the shoe that had been ruled out by the NBA – even though it hadn’t been – making it one of the most iconic designs ever produced.

Many believe this rich history around sneakers has imbued them with meaning that other clothing lacks. They have cultural value, giving them longevity in the marketplace and establishing loyal followers and fanbases.

Today sneakers are a status symbol, particularly in popular culture. In a recent hit single, Clash, the Brit award-winning rappers Dave and Stormzy begin: “Jordan 4s or Jordan 1s, Rolexes, got more than one.”

The British rap artist M1llionz says: “It has become a big competition over who can get the most exclusive trainers. People are more likely to listen [to your music] or watch your videos if they know you’re wearing limited-edition shoes – ones they haven’t seen before.”

Mist, a fellow rapper and sneakerhead, believes the rise of social media has put more pressure on musicians to invest in their image, especially footwear.

“Trainers have played a big part in my career,” he says. “People aren’t just fans of the music any more. They’re a fan of the music videos and how you’re doing it.” Mist’s video for the song Hot Property racked up more than 13 million views after fans shared it on social media, shocked that he had worn an expensive pair of Louboutin trainers on a dog sled in Iceland.

“People were, like, ‘Why has he got on Red Bottoms [Louboutin trainers] in three-foot snow with wolves?’ ” he says. “The trainers alone created such a hype.”

As well as celebrity backing, trainers are made popular by limiting the quantity produced. Even if a manufacturer can churn out half a million shoes for a fraction of the unit cost of making 5 000 – due to production, marketing and design costs – they won’t. They’ll deliberately maintain a high degree of scarcity.

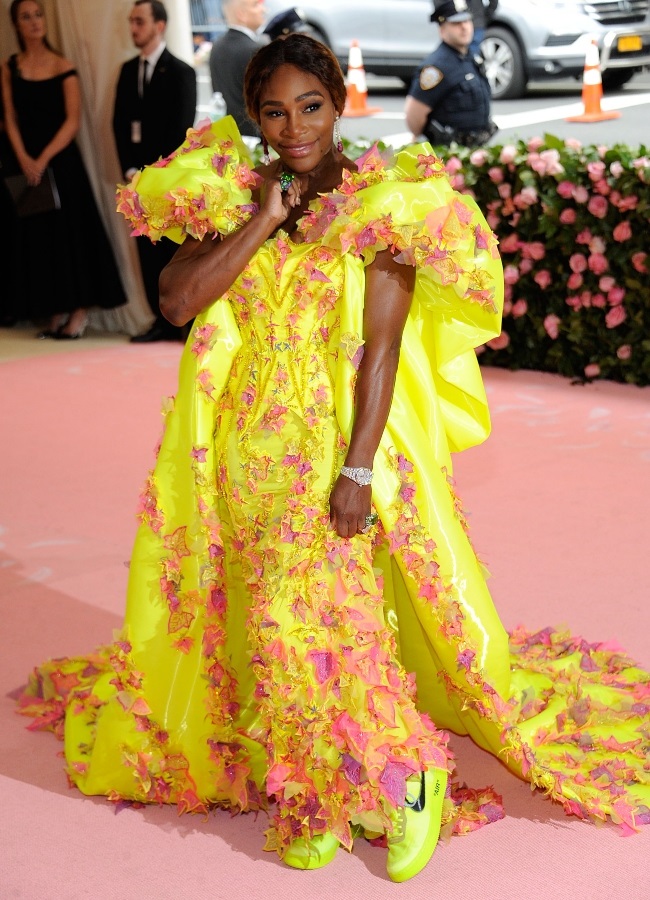

Trainers are now fully integrated through popular culture, no longer just a sports shoe. Tennis icon Serena Williams often wears them with ballgowns to red carpet events – and even sported a pair at her wedding.

Kylie Jenner, make-up billionaire and the youngest of the Kardashian clan, matches her exclusive footwear with her daughter’s. Instagram followers want whatever she’s got – and the tabloids try to determine her relationship status depending on that day’s choice of Nikes.

Sourcing limited-edition shoes is perhaps the most difficult part of reselling. Weeks before a new sneaker is released, celebrities such as the Kardashians will pop up on Instagram and in paparazzi photos wearing never-before-seen trainers that the brands have given to them. Eagle-eyed followers will notice this, then take to YouTube and Twitter to speculate on potential resale prices.

A release date for the shoe is set by the brand and prospective buyers will sign up to a virtual ballot offering the chance to buy one of the few thousand pairs of sneakers straight from the retailer.

The likelihood of “winning” a place, however, is slim.

“When I was in high school, I was having to skip class because I’d stayed up all night trying to get [in the queue for] a shoe,” says Hunter Carlisle, a 19-year-old reseller from Oklahoma. Now, though, he uses “bots” to increase his chances.

Bots – short for robots – are software programs that carry out automated repetitive tasks, imitating human user activity. They trick the brand’s website with computer code, allowing the user to re-enter themselves into the raffle hundreds of times over.

“For a drop tomorrow, I’m going to spend probably four hours just setting up all my servers and all the bots,” Carlisle says. “I’ll probably run about four or five.”

The high-school graduate has been so successful in the trainers industry that he recently bought himself a $150 000 (R2,2 million) BMW i8 sports car.

“More and more people recognise that reselling sneakers could be a viable option if you don’t want to go to college,” he says.

Niels Sodemann, CEO of the cyber-security firm Queue-it, says he has seen a significant rise in the use of queue-jumping bots over the past year.

“A sneaker drop on something pretty ordinary ended up having 23 million of what looked to be users in a queue from only two million different IP addresses,” he says. That is how many bots are being used.

Some resellers, however, will avoid the hassle of buying directly from the retailer altogether – they see it as time-consuming and expensive.

“I don’t have time for it,” says Omar from his Knightsbridge shop. “The botter has to sit on his computer all night preparing. I might as well sleep in till 11, call up all the botters once it’s over and then cash them out.”

He has spent a lot of energy building up a base of super-rich clients, so he can charge more for his trainers and make a good profit, even if he has to pay more to source them.

“This is why we’re in Knightsbridge, because I captured a large part of the Arab market, especially Qatari royalty,” says the business school graduate.”

Paying off staff at trainer shops is also common. Resellers will persuade shop assistants to set aside a couple of pairs on release day, which they can buy later when the queues have died down.

But the most trusted resellers will congregate on invite-only WhatsApp groups. Members on these forums will source their shoes in different ways — some use bots, others may pay off shop staff — but they will all have built a reputation in the market as reliable traders. Resellers and shops such as CNCPT can then mobilise these networks to source a specific model and size when a client wants it. Omar’s Knightsbridge store doesn’t hold any of its own stock, but instead relies on these external “consigners” to supply his customers.

When the 18-year-old reseller Fedor Makarov started out, he obtained his merchandise by waiting in queues for hours at a time. “I would camp outside these shops overnight,” he says.

He still remembers his first big win at the age of 14.

“It was the Yeezy Bred,” he says. “I went out at one in the morning to get them and I stayed until ten in the morning. I think my parents were very p*ssed at me that day.” He sold them on for £450 (R9 225), making almost £200 (R4 100) in profit.

Fedor now sources trainers from trusted WhatsApp groups, selling them on to Premier League footballers and famous rappers, a customer base he built up on Instagram.

He once travelled from London to Scotland just to get a photo of the Celtic FC player Karamoko Dembélé receiving his sneaker delivery. Being tagged on social media by a famous footballer with hundreds of thousands of followers increased his clientele and added legitimacy to his brand.

“I didn’t make any profit off the sale but he posted me [on Instagram],” Fedor says. “It got me 2 000 followers and that turned into 10 new customers.”

He decided to leave school to concentrate on his business.

“I found it more interesting to focus on hustling and making money – that was always my mentality,” he says. “Now I’m going to big parties. I’ve gone to parties with footballers.”

The truth is, anyone with the nerve and the capital to hold on to a limited-edition pair of sneakers has a chance of making money. The moment a shoe is worn it can no longer be traded as in mint condition on the resale market, meaning that scarcity goes up over time, and so do resale prices.

Mandeep Bahra works at a private investment office in Oxford and got into reselling by accident.

“I bought some sneakers on StockX for a 10 to 15 percent mark-up in 2019, then I realised I didn’t really like them,” he says. “I kept them and they went up by 300 percent in less than a year.”

“The joy of wearing and owning them” is what keeps him coming back for more, but many of the shoes he buys these days never come out of their paper wrapping.

“I have about 13 pairs still in boxes that I had seen in the store and then thought, actually they’re not for me.”

The investor keeps them in brand-new condition ready to resell when the price is right.

“I don’t mind holding on to them.”

Carlisle points out that subscriptions to his sneaker training course, which teaches hundreds of prospective resellers how to get their hands on the rarest items, grew fivefold last year during the pandemic.

These so-called “cook groups” are set up by well-known resellers who charge a fee to explain how to source and sell trainers online using bots.

A survey last year by the Harris Poll showed that 23 percent of US adults have, or plan to purchase, limited-edition sneakers, and 37 percent of these said they were motivated by the investment opportunity.

Others think the market is too volatile to provide any long-term investment opportunities – not everyone comes out of the business unscathed. Omar and David say that one established reseller in London was badly hit after Adidas released a second batch of a limited-edition shoe without warning.

The Adidas x Pharrell Williams Human Race NMDs were doing well when their reseller friend first secured 300 pairs, Omar recalls. But then the unthinkable happened.

“Suddenly [Adidas] flooded the market and every single one of those shoes crashed in price – we’re talking £3 000 (R61 500) to £400 (R8 200) a pair.”

Investors and resellers are, ultimately, at the mercy of the brands and cultural shifts. The market is unpredictable and vulnerable to manipulation. Fakes plague the industry, and “backdooring” – the practice of releasing a large number of limited-edition sneakers before official release – enables a select group of resellers to dictate the price before the shoes are even made public.

Despite such drawbacks, many still see sneaker trading as a risk they are willing to take. “We’re in a marketplace,” Omar says. “If you understand economics, you understand sneakers.”

© THE SUNDAY TIMES/NEWS LICENSING

JOIN THE YOU BOOK CLUB | Sign up for our free weekly books newsletter and get access to reviews, author interviews, book extracts and giveaways

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners