Extract taken from S.A. Politics Unspun and published with permission from Two Dogs, an imprint of Burnet Media.

For more information about the book, scroll to the bottom.

Also read part 1 and part 3

How elections work: into the action

All elections are formally controlled by the Independent Electoral Commission, the members of which are appointed a bit like judges: parties get to nominate candidates, there are public hearings, and so on.

The IEC itself is a marvel. The only organisation that comes close to it in South Africa in terms of efficiency and getting the job done is the South African Revenue Service. If you think about what the IEC has to do, it’s not a job for the faint-hearted.

You have to arrange for every single South African adult who wants to vote to be able to cast a ballot in exactly the same way, all over the country, on the same day.

Fairly straightforward in Sandown and Constantia, but pretty tricky in the rural Eastern Cape or KZN.

To do this, the IEC goes to communities, finds people who are considered trustworthy by those communities, and appoints them as electoral officers.

They are trained and paid, and given the power to run the voting booths themselves. In doing so, they make decisions on the ground, hold media interviews and basically run the show.

It’s completely different to the usual political arena, where ordinary party members are told to shut up and the flow of information is tightly controlled.

South Africa’s biggest polling station, by number of people served, is at Joubert Park in Johannesburg. More than 5,000 people living in the flats in the area are registered to vote there. In this case, three separate polling booths are set up, under a series of IEC gazebos.

The man who runs it, Patrick Phosa (no relation to any other influential Phosa), works at the City of Johannesburg usually but takes time off to work for the IEC. By 5am on the morning of an election he’ll already be there, making sure everything’s ready.

The first queue normally forms an hour later, and when voting starts, at 7am, there are several hundred people in line. There are similar scenes in informal settlements around Gauteng, and in all the rural areas around the province.

Voting is allowed to continue until around 7pm, when the counting starts. Even then, the IEC will try to ensure that people already in the queue are allowed to vote. If necessary, the police, or even soldiers, will surround the queue to allow those in it to vote, while stopping anyone else from joining that queue.

Votes are counted at the polling stations themselves. Political parties are allowed to have representatives there to ensure that everything is kosher, and they get to watch the counting. By this stage everyone’s been awake for over 24 hours and they can get a little nuts.

It’s common to see representatives from the DA and the ANC, who’ve been slagging each other off for months, sharing chairs and phone chargers and generally becoming friends. For just a few short hours.

The nerve centre of this counting operation is the IEC headquarters, normally at the Pretoria Showgrounds (now the Tshwane Events Centre), where every single political leader worth his or her salt goes to watch the massive scoreboard in the front of a cavernous hall.

TV and radio stations usually fight for the best space, but the brilliantly organised IEC manages to keep most people happy.

They also employ magical IEC fairies who provide three meals a day – and one in the middle of the night! – for everyone working there, most of them getting by on no sleep whatsoever.

With every national political leader there, it’s also a chance to mend a few fences after the mud (and poo) throwing of the last few months.

The nerve centre is there to collate all the results as they come in. Using the IEC’s computer system – which is made available on the web at www.elections.org.za – you can see not just the national and provincial results, but how people voted in individual polling stations.

If you drill down through the data far enough, you actually get a scan of the document signed by the electoral officer for that station.

This means that you can extrapolate not just how a party did across the country or even in regions, but how it did in very specific areas.

This is how it was possible to work out that the ANC almost lost the vote in Port Elizabeth during the 2009 national elections, which meant the party knew it had to campaign very hard there in the 2011 local government polls.

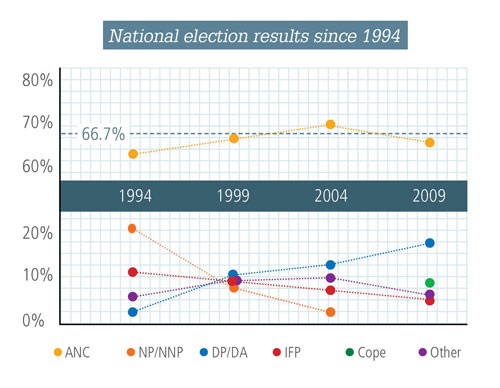

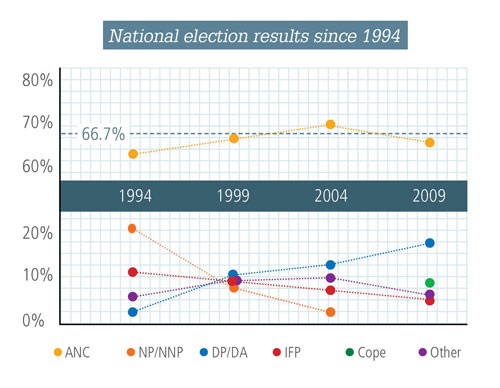

As the counting continues, it usually becomes pretty obvious by the afternoon after the elections what the final outcome is going to be, and how much the ANC has won by. While the numbers on the scoreboard swing back and forth for a while, it should be clear within 24 hours what the majority will be and how much the playing field has changed.

At some point the IEC stops the scoreboard and then starts to prepare for its final announcement. There is some careful choreography here. The chair of the IEC makes the final announcement and then hands over the results of the election to the president of the country.

This all takes place at one podium. The president goes through the ritual of thanking the IEC, appearing all very presidential in the process. Then the entire show shifts to another stage, where the president, now wearing his ANC leader hat, gives a completely different speech.

It’s one of those moments when protocol is very important. The president has to represent the country at one moment, the winning party at another.

When the counting is finally over, it’s time to work out how it all translates into seats in the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces.

This is done according to a mathematical formula that sees around 20 million votes cut down to 400 seats in the National Assembly. It can boil down to quite minute percentages at times, but the formula is supposed to favour the smaller parties ever so slightly to give them a better chance at representation and thus increase diversity.

To contest an election, each party has to provide the IEC with a list of 400 names of people who would represent it in Parliament should it (hypothetically…) win every vote in the country. Within the bigger parties it’s hugely important for ambitious politicians to get on that list, and there are some rather vicious fights within the ANC and the DA over how the process works.

If you’re not high enough you won’t become an MP, and then you can’t become a minister either. Once the seats are allocated to the lucky 400, the country’s new MPs then go through to Parliament where they will represent their parties in the votes that follow.

Read: part 1; part 3

About the book:

South African politics is a murky, convoluted, complicated, cut-throat world that not many people fully understand.

- How does it all work?

- What does Trevor Manuel actually do these days?

- Is Julius Malema really finished?

- Will Cyril Ramaphosa be our next president?

- How long will Jacob Zuma rule for?

- Who really matters in our politics?

- And what’s going to happen at the next elections?

Premier SA political analyst and commentator Stephen Grootes cuts through the incomprehensible political spin and media coverage out there to provide an accessible, attractive, easy-to-read road map to South African politics.

Visit Kalahari.com to purchase a copy of S.A. Politics Unspun.

Read this book yet? Tell us what you thought of the book in the comment box below.

Sign up for Women24 book club newsletter and stand a chance to win our top ten books from kalahari.com.

Follow Women24 on Twitter and like us on Facebook.

For more information about the book, scroll to the bottom.

Also read part 1 and part 3

How elections work: into the action

All elections are formally controlled by the Independent Electoral Commission, the members of which are appointed a bit like judges: parties get to nominate candidates, there are public hearings, and so on.

The IEC itself is a marvel. The only organisation that comes close to it in South Africa in terms of efficiency and getting the job done is the South African Revenue Service. If you think about what the IEC has to do, it’s not a job for the faint-hearted.

You have to arrange for every single South African adult who wants to vote to be able to cast a ballot in exactly the same way, all over the country, on the same day.

Fairly straightforward in Sandown and Constantia, but pretty tricky in the rural Eastern Cape or KZN.

To do this, the IEC goes to communities, finds people who are considered trustworthy by those communities, and appoints them as electoral officers.

They are trained and paid, and given the power to run the voting booths themselves. In doing so, they make decisions on the ground, hold media interviews and basically run the show.

It’s completely different to the usual political arena, where ordinary party members are told to shut up and the flow of information is tightly controlled.

South Africa’s biggest polling station, by number of people served, is at Joubert Park in Johannesburg. More than 5,000 people living in the flats in the area are registered to vote there. In this case, three separate polling booths are set up, under a series of IEC gazebos.

The man who runs it, Patrick Phosa (no relation to any other influential Phosa), works at the City of Johannesburg usually but takes time off to work for the IEC. By 5am on the morning of an election he’ll already be there, making sure everything’s ready.

The first queue normally forms an hour later, and when voting starts, at 7am, there are several hundred people in line. There are similar scenes in informal settlements around Gauteng, and in all the rural areas around the province.

Voting is allowed to continue until around 7pm, when the counting starts. Even then, the IEC will try to ensure that people already in the queue are allowed to vote. If necessary, the police, or even soldiers, will surround the queue to allow those in it to vote, while stopping anyone else from joining that queue.

Votes are counted at the polling stations themselves. Political parties are allowed to have representatives there to ensure that everything is kosher, and they get to watch the counting. By this stage everyone’s been awake for over 24 hours and they can get a little nuts.

It’s common to see representatives from the DA and the ANC, who’ve been slagging each other off for months, sharing chairs and phone chargers and generally becoming friends. For just a few short hours.

The nerve centre of this counting operation is the IEC headquarters, normally at the Pretoria Showgrounds (now the Tshwane Events Centre), where every single political leader worth his or her salt goes to watch the massive scoreboard in the front of a cavernous hall.

TV and radio stations usually fight for the best space, but the brilliantly organised IEC manages to keep most people happy.

They also employ magical IEC fairies who provide three meals a day – and one in the middle of the night! – for everyone working there, most of them getting by on no sleep whatsoever.

With every national political leader there, it’s also a chance to mend a few fences after the mud (and poo) throwing of the last few months.

The nerve centre is there to collate all the results as they come in. Using the IEC’s computer system – which is made available on the web at www.elections.org.za – you can see not just the national and provincial results, but how people voted in individual polling stations.

If you drill down through the data far enough, you actually get a scan of the document signed by the electoral officer for that station.

This means that you can extrapolate not just how a party did across the country or even in regions, but how it did in very specific areas.

This is how it was possible to work out that the ANC almost lost the vote in Port Elizabeth during the 2009 national elections, which meant the party knew it had to campaign very hard there in the 2011 local government polls.

As the counting continues, it usually becomes pretty obvious by the afternoon after the elections what the final outcome is going to be, and how much the ANC has won by. While the numbers on the scoreboard swing back and forth for a while, it should be clear within 24 hours what the majority will be and how much the playing field has changed.

At some point the IEC stops the scoreboard and then starts to prepare for its final announcement. There is some careful choreography here. The chair of the IEC makes the final announcement and then hands over the results of the election to the president of the country.

This all takes place at one podium. The president goes through the ritual of thanking the IEC, appearing all very presidential in the process. Then the entire show shifts to another stage, where the president, now wearing his ANC leader hat, gives a completely different speech.

It’s one of those moments when protocol is very important. The president has to represent the country at one moment, the winning party at another.

When the counting is finally over, it’s time to work out how it all translates into seats in the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces.

This is done according to a mathematical formula that sees around 20 million votes cut down to 400 seats in the National Assembly. It can boil down to quite minute percentages at times, but the formula is supposed to favour the smaller parties ever so slightly to give them a better chance at representation and thus increase diversity.

To contest an election, each party has to provide the IEC with a list of 400 names of people who would represent it in Parliament should it (hypothetically…) win every vote in the country. Within the bigger parties it’s hugely important for ambitious politicians to get on that list, and there are some rather vicious fights within the ANC and the DA over how the process works.

If you’re not high enough you won’t become an MP, and then you can’t become a minister either. Once the seats are allocated to the lucky 400, the country’s new MPs then go through to Parliament where they will represent their parties in the votes that follow.

Read: part 1; part 3

About the book:

South African politics is a murky, convoluted, complicated, cut-throat world that not many people fully understand.

- How does it all work?

- What does Trevor Manuel actually do these days?

- Is Julius Malema really finished?

- Will Cyril Ramaphosa be our next president?

- How long will Jacob Zuma rule for?

- Who really matters in our politics?

- And what’s going to happen at the next elections?

Premier SA political analyst and commentator Stephen Grootes cuts through the incomprehensible political spin and media coverage out there to provide an accessible, attractive, easy-to-read road map to South African politics.

Visit Kalahari.com to purchase a copy of S.A. Politics Unspun.

Read this book yet? Tell us what you thought of the book in the comment box below.

Sign up for Women24 book club newsletter and stand a chance to win our top ten books from kalahari.com.

Follow Women24 on Twitter and like us on Facebook.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners